|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/stone743.jpg

http://www.cruithni.org.uk/overview/over_5.html

http://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/vikings/ship.html

http://www.regia.org/vikings.htm

http://www.legends.dm.net/sagas/viking.html$

http://www.lkf.lv/vikingi/ENG/diary.html

http://www.mnh.si.edu/vikings/index2.html

http://www.think-ink.net/norway/oslo/oslo5.htm

http://www.cjicollectibles.com/vivishcotath.html

http://www.rowinghistory.net/vikings.htm

http://homepage.powerup.com.au/~rhayes/vikingb/vikshipl.htm

|

The Nordic Countries The Vikings The

Vikings have been an endless source of inspiration for writers as well as

other artists, and in recent decades the Viking Age has been popular amongst

film makers who have usually portrayed their darker sides. Descriptions

of the Vikings came mostly from their victims; monks, merchants, peasants and

others who got in the Vikings' way. The famous Icelandic Sagas describe the

Vikings as heroic, virtuous characters; however, one must bear in mind that

the Sagas were written some centuries later than the events were supposed to

have occurred and are rather considered as literature than history. The

first Viking expeditions took place in the late 8th century and continued for

almost three hundred years, during which time the Vikings harassed nations of

islands, coastlines and riverbanks. |

For their raids they would choose locations with the

minimum risk of resistance, and had usually concluded their mission and

disappeared by the time the victims could call for help. These

tactics yielded easy plunder, and rumours of their methods spread quickly,

causing exaggerated reports of numbers of men and ships. Their

techniques in shipbuilding were immensely advanced and their ships were by

far the fastest at that time. They crossed the open seas even though land

could not be seen for days; whether courage or greed was the driving force is

disputable. Archaeological

finds and contemporary reports prove that the area plundered by the Vikings

was vast, from |

'A furore normannorum libera nos domine''Skona oss herre från nordmännens raseri''Oh lord, save us from the rage of the Nordic people'

[A common prayer in the

French churches during the 9th century.]

Perhaps the best known

period of Swedish history (internationally), is the time of the Vikings (no,

not the football team in America). The stereotype Viking is a tall blond figure

possesed with a raging fury which he releases upon other countries..

Although this period was

short compared to the rest of the long history of Sweden, it is one of the most

widely known.

The 8th of June was a

beautiful summer day on the holy Island of Lindisfarne, situated on the

Northumberland coast in the north east of England. It had a monastary which was

founded in the 6th century and was famous for the fact that some of the finest

literature of its time came from here. Some of the books written there are

still intact and readable. The monks, who didn't suspect anything unusual, went

down to the shore to greet the strangers who had arrived.

This is what an author said

about 100 years later: 'The same year the heathens arrived from the north to

Brittany with a fleet of ships. They were like stinging wasps, and they spread

in all directions like horrible wolves, wrecking, robbing, shattering and

killing not only animals but also priests, monks and nuns. They came to the

church of Lindesfarne, slayed everything alive, dug up the altars and took all

the treasures of the holy church'. The Vikings had arrived.

The attack wasn't the

first. Numerous smaller attacks had been made earlier. However, they tended to

be rather sporadic. This was something completely different. The attack came as

a shock to the rulers of Brittany and the rumours about the fearless Nordic men

spread over Europe.

The French king Karl the

Great had an English adviser by the name of Alcuin. As soon as he heard of the

attack on Lindesfarne, he wrote: 'In nearly 350 years we and our forefathers

have been living in this the best of countries and never before has such terror

struck Britain as the one we now have to suffer from this heathen race. Nor was

it thought to be possible that such an attack could be carried out from the

sea. Look at S:t Cuthbert's church sprinkled with the blood of the holy

priests, deprived of it's decorations, a room more venerable than any in

Britain given as spoils to this Heathen race'.

The next year the Vikings

returned and plundered the convent in Jarrow, just a few miles from

Lindisfarne. This was the real start of the Viking Age. The Vikings were to be

the first Europeans who passed the winter in Labrador and New foundland. They

populated Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, the Shetland Islands, Orkney,

the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. They founded states in Ireland and in

Britain. They conquered Normandy in France and founded a dynasty which lived

and ruled far into the Middle Ages. They built merchant towns in Birka

(Sweden), Hedeby (Denmark) and Kaupang (Norway). They even founded the first

colony in America long before anyone else in Europe even thought that there

existed land that far westwards.

Vikings also founded

kingdoms in Russia and built trade stations along the rivers all the way down

to the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. They went to Constantinople and Bahgdad,

Gurgan and Chorezm. They even came into contact with Byzantium and they formed

a feared elite regiment for the East Roman Emperor, a guard which existed for

some hundred years. They conquered London, besieged Lisbon, burnt Santiago,

assaulted Seville, attacked Mallorca, and sold European slaves in North Africa.

They terrorized Paris (on numerous occasions) and burnt Hamburg and many other

German cities. They even went to Jerusalem and possibly also to Alexandria.

During a quarter of a

century, from 8th June 793 until 15th October 1066, these men would come in

waves, often young and seeking a fight, and extremely skilled as sailors and

warriors. Their activities left traces for eternity. Over 900 of the most

common English words come from the Vikings (sky, skin, scrape, skirt, husband

(husbonde) and window (vindue) are some examples). There are over 600 village

names in England which can be directly related to the Vikings (Grimsby,

Thoresby, Brimtoft, Langtoft and so on). There are English counties where about

75 percent of the village names derived from the Vikings. On the Shetland

Islands the percentage goes up to about 99 percent. In the North East of

England the Nordic languages were spoken until as late as the 12th century, on

the Isle Of Man until the middle of the 15th century.

In Normandy there are still

village names which have their originn in the Nordic countries like: Dalbec,

Runitot, Bourguebu (Borgeby) and sex la londe (av lund, offerlund). And every

French sea captain still gives the commands 'babord' and 'tribord' when he

means left and right.

In Russia, which was

founded by the people from Rus (the Swedish Roslagen County), millions of

people still hold the name Oleg, Olga and Igor - from the names of the Viking

gods Helge, Helga and Ingvar. When Russians politely address each other as

'gentlemen', the word comes from the Viking word 'husbonden'.

Foreigners have never

stopped wondering about and being fascinated by the Vikings. They have been

called the Giants from the North, 'heathens', 'savages', 'the first knights'

and so on. They have been described as barbarians but also as noble poets with

female goddesses. Even today some French schoolbooks explain the Viking

temperament in terms of the climate in which they lived. Since they came from

such barbaric, cold and boring (!) countries, they were forced to break the

melancholy by a bit of good old fashioned slaughtering of innocent people (and

getting some sun into the bargain!).

As always, their

(admittedly) enormous success as traders and warriors can't be easily

explained. How was it possible for such a small population of perhaps about .8

million inhabitants to instil the feeling of fear the way they did throughout

the whole of Europe? At the beginning of the Viking era there were no united

kingdoms in Scandinavia, and the people who went out on crusades were a

minority. Most people spent their time at home, farming and trying to run the

matters in general.

One of the main reasons for

their success is the fact that Europe at the time had a hard time getting

united. As it was, many small kingdoms fought with each other to form a big

country. The Vikings, who from birth were taught how to fight well (and

encouraged by their religion to do it) and how to manouvre a boat (which by the

way was by far the best ever built in Europe by that time, possibly even the best

in the world), were given rather easy targets. When they started to take horses

on board the boats, the Vikings were more or less invincible when attacking a

town, especially as the attacks came very suddenly and often from the open sea

by boats which could travel at a good 15 knots all the way in to the shore.

The boat was one of the key

factors behind their success. It was a long, rather narrow boat built of oak. The

boat building skills had been developed over hundreds of years in countries

where the only practical way of travelling was by boat. When the wind was not

blowing it was possible to row the boats, and when the wind came from the stern

the boats were very fast. They didn't need deep water (normally a Viking boat

could be used as a landing vehicle) and they could still take a heavy load. They

were very easy to manouvre and they could carry large numbers of warriors

(there were boats which could take a crew of up to 200 men or more).

Life on board was rather

hard. The normal boat was about 30 metres long and had a maximum width of five

metres at the broadest place. The Vikings ate dried and salted meat, and fish

which was caught en route. For drink they usually had sour milk, water and beer

(or mead). To prevent scurvy they ate cloudberry and a plant called cochleria

officinalis. The only protection from the weather was a small tent (in the best

of cases). Every man had his own chest with his personal belongings. The chest

also served as the bench they sat on when they had to row the boat. The ship

was steered by a large oar on the right side, therefore called 'styrbord'

(starboard), and the first mate's back pointed to 'babord' (the port side). At

the stem and the stern there were small platforms named 'lyftingar'.

There were many types of

boats. In an attack fleet there usually was a couple of battleships with long

and narrow design so as to be fast and able to take many men. Then there were

the merchant ships which were much broader so that they could take a great load

(up to 20000 kilograms of weight). These boats were called 'knarr', possibly

because of the sound that they made when they moved in the sea.

The navigation was handled

by specially trained personnel who mostly navigated by the stars and the sun. Sometimes

they brought birds with them which they let go and then followed to the nearest

shore. They had peloruses (astonishingly similar to the ones used today) and

the famous 'sun stone'. The latter was thought to be a fraud, but later

findings make it clear that it wasn't. The sun stone is a mineral found in

Iceland or Norway which could polarize the sun light. That way you could see

where the sun was even if it was cloudy and the sun itself was not visible to

the naked eye.

To measure the sailed

distance they used their experience when studying the wash (The flow of water

around the stem). But there were no exact methods to measure the speed. Usually

the Vikings followed the coasts as closely as possible, but they weren't afraid

to make long voyages over the open sea without any contact with land if they

had to.

In the

period from 800 to 1050 A.D., the Nordic peoples made their dramatic entry into

the European arena. They stormed forth, terrorizing well-established societies

which were accustomed to war, but not to the startling tactics of the Vikings.

However, contact between

Scandi-navia and the rest of Europe was nothing new. Archaeological findings

show that trade and cultural influence can be traced back several millennia

B.C. Nevertheless, the Nordic area was a distant outpost with little political

and economic value for the rest of Europe.

This picture changed

shortly before the year 800. In 793, the Lindisfarne Monastery on England's

east coast was pillaged by foreign seafarers, and at the same time we find the

first recorded reports of raids elsewhere in Europe. The chronicles and tales

of the next 200 years are studded with alarming accounts of the Vikings. Ships,

sailing in large as well as smaller groups, attacked all the coasts of Europe. The

Vikings sailed up the rivers of France and Spain, conquered most of Ireland and

large sections of England, and took control of areas skirting rivers in Russia

and the Baltic coast. There are narratives of raids in the Mediterranean, and

as far east as the Caspian Sea. Norsemen starting out from Kiev, were even

fool-hardy enough to attempt an attack on Constantinople, the capital of the

Byzantine Empire. Eventually, the plundering raids were replaced by

colonization. Place names reveal a large Viking population in the North of

England, centred around York. Farther south in Britain, a large area was called

The Danelaw. The French king gave Normandy as a fief to a Viking chieftain so

that he would keep other Vikings away. The islands north of Scotland developed

a mixed Celtic-Norse population, and thriving societies were established on

Iceland and Greenland.

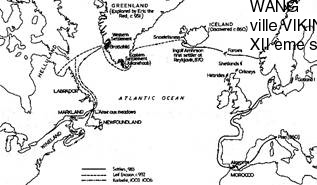

The furthest westward drive

ended with the unsuccessful attempt at found-ing a settlement in North America.

Around 1000 A.D., people from Iceland or Greenland discovered land to the west,

and the sagas tell of several journeys including attempts to plant roots in the

new land. Conflicts arose between these colonists and the indige-nous Indians

or the Eskimos, and the newcomers gave up.

Attempts at pinpointing the

location of the Norsemen's settlement have led to such varied results as

Labrador and Manhattan, in accordance with different interpretations of the

Icelandic sagas. In the 1960s, Anne-Stine and Helge Ingstad found the site of

early homesteads on the north coast of Newfoundland. Excavation showed these to

be the same sort of buildings found on Greenland and Iceland. In addition,

Nordic artifacts were exca-vated at the site and dated at circa 1000 A.D.

Whether these are traces of the settlements mentioned in the sagas, or from

other journeys which we have no record of, is impossible to say. However, the

finds prove that Nordic seafarers really sailed to the North American

Con-tinent around the year 1000, as narrated in the Icelandic sagas.

Overpopulation and a

scarcity

What are the reasons for

this violent expansion within a few generations? Stable states such as France

or the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in England appear to have fallen easily to the

swords of the attackers. As might be expected, the picture handed down to us in

written accounts is tainted by this the Vikings are portrayed as terrible

robbers and bandits. And indeed they were. But they must have had other traits

as well. Some of their leaders were certainly extremely skilful organizers. An

effective military tactic could win a battle, but the Vikings founded kingdoms

in conquered territories. Some did not survive the Viking period, such as the

kingdoms based in Dublin and York. But Iceland is still a thriving nation. The

Viking kingdom in Kiev formed the basis of the Russian empire, and traces of

the organizational talent of the Viking chieftains are clearly visible today on

the Isle of Man and in Normandy.

The remains of fortresses

which could be used as a meeting place for large armies -- dated to the end of

the Viking period -- have been found in Denmark. The fortresses are circular

and divided into quadrants, with square buildings in each of the four sections.

These castles were placed with a precision testifying to the rulers' advanced

sense of order and system. There must have been a knowledge of surveying

techniques and geometry in the court of the Danish King.

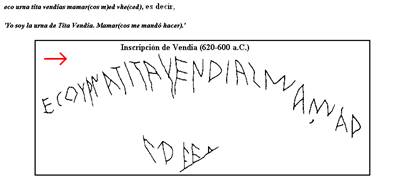

In addition to the

West-European narratives, we have written sources from other Viking

contemporaries -- from travelling Arabs and from Byzantium. Short inscriptions

have been left us in the homeland of the Vikings as well -- the runes carved in

wood and stone. The saga tales of the 12th and 13th centuries also have much to

tell us about the Viking age, even though they are written several generations

after the period which they depict.

The Vikings came from what

is now Denmark, Sweden and Norway. Theirs was a self-sustaining agricultural

society, where farming and cattle breeding were supplemented by hunting,

fishing, the extraction of iron and the quarrying of rock to make whetstones

and cooking utensils. Even though the farmers were generally self-reliant, some

goods were traded -- for instance salt -- a necessity for man and cattle alike.

Salt is an everyday item which would not have been imported from a greater

distance than necessary, whereas luxury items came from further south in

Europe. Iron, whet-stones, and steatite (soapstone) cooking pots were important

export products and were an essential contribution to a trade growth in the

Viking age. Even in periods when Viking raids abounded trade was conducted

between West Europe and the homeland of the Vikings. One of the few reports we

have about condi-tions in Norway in Viking times was orated by the North

Norwegian chief-tain, Ottar. He visited King Alfred of Wessex as a peaceful

trader, at the same time as Alfred was waging war with other Viking chieftains.

It has been suggested that

the expan-sion of the Viking age was spurred by a population growth outstepping

the capacities of domestic resources. Archaeological evidence shows that new

farms were cleared in sparsely populated forest areas at the time of the

foreign expansion -- so the pressure of population growth is surely a

contributing factor. Iron extraction is another. An abundance of iron to forge

weapons and arm everyone setting off on raids helped give the Vikings the upper

hand.

The tactical advantage

of the Viking ships

Shipbuilding in Scandinavia

also contributed to the tactical superiority of the Vikings. A well-known

Swedish archaeologist has written that the Viking ships are the only seaworthy

amphibious landing vessels ever to be used by invasion forces. Even though this

is an exaggeration, it explains much of the secret of the Vikings' military

superiority. Many of the accounts of Viking attacks appear to support this

theory. The element of surprise was essential. A swift on-slaught from the sea

with light ships, which were independent of harbours -- and could thus approach

a coast where they were least expected -- and beating a quick retreat before a

counter-offensive could be launched; this was the tactic.

Spheres of interest

developed between Danish, Swedish, and Norwe-gian Vikings -- even though groups

from all three nations often partici-pated together when the most renowned

chieftains set sail. The Swedes sailed mainly to the east, and they controlled

the eastern trade routes via the waterways leading into Russia. Large amounts

of Arabian silver coins in Swedish archaeological diggings testify to intensive

trading. The Danes sailed to the south, to Friesland, France and Southern

England, while the Norwegians headedto the west and northwest, to Northern

England, Scotland, Ireland, the Orkneys, Shetlands, and Faroes.

The ships were not only

necessary for raids and trade, but also a pre-requisite for successful

colonization, when entire families with all their possessions and livestock

sailed away to new lands. The perilous voyages across the North Atlantic to the

Orkneys, Shetlands, Faroes, Iceland and Greenland testify that the

ship-builders of the Viking age not only could build ships which were

swift-sailing and capable of attacks in the North Sea area, but extremely

sea-worthy vessels as well. Colonization followed when seafarers discovered new

land, or men returned from trading or raids and spread news of bountiful

conditions abroad.

In certain areas, the

Vikings appear to have displaced the original inhab-itants. In others, such as

Northern England, it seems that the Norsemen's main enterprise was cattle

breeding and they utilized land of little use to the indigenous

grain-cultivating farmers.

Those who journeyed to

Iceland and Greenland found virgin soil. With the possible exception of a few

Irish monks on Iceland -- who soon "left because they did not want to have

heathens as neighbours" -- Iceland and the parts of Greenland colonized by

the Vikings appear to have been uninhabited when the Norsemen arrived.

The contemporary references

we have about the Vikings stem predominantly from sources in Western Europe who

had bitter experiences with the invaders, and we are undeniably presented with

the worst side of the Vikings. Archaeologi-cal excavations both in the

homelands of the Vikings and in their new settle-ments give more nuance to this

picture. We have finds from homesteads, farms, and market places where lost or

discarded articles tell of a common everyday life. Traces have been found

testifying to iron extraction in moun-tain areas, where iron ore in bogs

combined with ample firewood from forests to form the basis of a flourish-ing

industry. Quarries where soapstone was gathered for pots and exception-ally

fine whetstones have also been found and analyzed. In some fortunate

circumstances we have found ancient agricultural fields in areas later left to

nature. In such places we can find the piles of stones once painstakingly

cleared away from fields, and with enough care, we even uncover the furrows

left by Viking ploughs.

Towns and kingdoms

As the Viking period

progressed, society changed. Leading chieftain families accumulated land and

power, forming the basis for kingdoms, and the first towns were founded. From

Staraya Ladoga and Kiev in Russia, to York and Dublin in the British Isles, we

can piece together the daily life of the townspeople. Market places and towns

were based on craftsmanship and trade. Even though the town-dwelling Vikings

probably kept cattle, farmed and fished to meet their house-hold needs, the

towns certainly depended on agriculture supplies from outlying districts. In

South Norway was the marketplace Kaupang, near Larvik, mentioned in Ottar's

narrative to King Alfred. Kaupang never became more than a marketplace, while

Birka near Malaren in Sweden and Hedeby at the German-Danish border could be

called towns. Both were abandoned at the end of the Viking period, but Ribe in

Denmark's Vest Jylland thrives today as of course do York and Dublin. In these

towns we find well regulated areas with clearly defined plots of land, roads

and surrounding fortifi-cations. Some of the towns have obviously been planned.

Many are well established in accordance with the orders of the kings who

personally -- or by means of trusted aids -- had their say in town planning and

the distribution of plots. We can see that renovation and garbage disposal was

given less attention than town planning -- waste can be found in thick layers. In

contemporary times, the stench must have been most uncomfortable. Today we find

clues to everyday conditions, from the rubbish of various craftsmen to fleas

and lice -- and we can piece together the way life was. We find objects which

must have come from afar, such as Arab silver coins and Byzantine silk, heaped

together with the products of local blacksmiths, cobblers and comb-makers.

The Norse gods

At the end of the Viking

age, Chris-tianity was generally accepted in the Nordic countries. It replaced

a heathen religion, with a pantheon of gods and goddesses who each had power over

their own domains. Odin, old and wise, was the chieftain of them all. Thor was

the god ofthe warriors, while the goddess Froy was responsible for the

fertility of the soil and livestock. Loki was a trickster and a sorcerer,

unreli-able and distrusted by the other gods. The gods had dangerous

adversaries -- the jotuns -- representing the darker side of life.

The heathen gods are best

known from descriptions written down in early Christian times, and perhaps

coloured by the new faith. Farm names such as Torshov, Frøyshov and Onsaker

have kept their original heathen god names. Present day Norwegian place names

with the last syllable "hov" indicate that there once was a heathen

temple at the site.

The gods had human traits,

and like their Greek counterparts on Olympus they lived a raucous life. The

gods fight, eat and drink. Mortals who fell in battle, went straight to the

table to feast with the gods, and burial tech-niques clearly tell us of a need

for the same paraphernalia in the life after death as here on earth. In the

Viking age, the dead could be buried or cremated, but burial gifts were

necessary in either case. The amount of equipment the dead took with them

reflects their status in life as well as different burial traditions. In

Norway, the burial traditions were especially rich. As a result, graves are a

prolific source of knowledge about the everyday life of the Vikings. Every-thing

provided for use in the afterlife provides us with a window into the world of

the Vikings -- even though time has taken its toll and often only remnants are

left of the buried objects.

The grave remnants supplement our material from excavated living sites. In

these sites -- both in towns and on farms -- we find misplaced or damaged

articles, remains of houses, waste from food making and crafts-manship, and in

the graves we uncover some of the finest personal effects of the deceased.

A violent society

An indication of the violent nature of society is the fact that nearly all

the graves of males include weapons. A well-equipped warrior had to have a

sword, a wooden shield with an iron boss at its centre to protect the hand, a

spear, an axe, and a bow with up to 24 arrows. The helmets and coats of mail

with which most Vikings are commonly portrayed in modern pictures, are

extremely rare in archaeological material. Helmets with horns, ubiquitous in

present-day depictions, have never been found amongst relics from the Viking

period. Even in the graves with the most impressive array of weapons, we find

signs of more peaceful activities: sickles, scythes, and hoes lie along side of

weapons. The blacksmith was buried with his hammer, anvil, tongs, and file. The

coastal farmer has kept his fishing equipment and is often buried in a boat. In

women's graves we often find personal jewelry, kitchen articles and artifacts

used in textile production. Women too, are often buried in boats. Wooden

articles, leather goods, and textiles generally do not survive the soil, so

there are many gaps in our knowledge.

In a smattering of graves, the soil-type has been more conducive to

pre-servation. In many areas along the Oslofjord, we find blue clay directly

underneath the turf, dense and nearly impermeable by water and air. A few

graves are well preserved after a thousand years, and we have retained a whole

spectrum of articles placed in the pit. The treasures from the enormous Viking

ship graves from Oseberg, Tune, and Gokstad -- which can be seen at the Viking

Ship Museum at Bygdøy in Oslo -- are prime examples of what gifts can be

preserved for future generations, given the right soil conditions. We do not

know who the dead were, but they obviously belonged to the upper echelon of

their society. Perhaps they belonged to a royal family which, a few generations

later, unified Norway as one nation.

The graves at Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune have recently been dated by analysis

of the annual rings in the oak material. The Oseberg ship was built around

815-820 A.D. The burial has been dated to an exact year - it was in 834. The

Gokstad and Tune ships were constructed in the 890s and were placed in the

graves right after 900 A.D. In these three graves, big ships were used as grave

repositories.

Only the hull of the Tune ship has been preserved, and the grave was robbed

earlier of nearly all its items, but enough remained for us to see that the

ship was originally of the same fine quality as the two others. The Tune ship

was about 20 metres in length. The Oseberg ship's length is about 22 metres and

the Gokstad ship is 24 metres long.

At the time of burial, the ship was drawn up on land and placed in a pit. A

burial chamber was constructed behind the mast, where the deceased was placed

to rest in a bed, dressed in finery. Copious provisions were placed in the

ship, dogs and horses were sacrificed, and a large burial mound was piled on

top of the vessel.

An Arab travelling in Russia at the end of the 9th Century happened upon a

group of Vikings who were in the process of burying a chieftain in this manner.

Ibn Fadlan made note of his observations, and his journal has survived. The

deceased chieftain's ship was pulled ashore, and valuables were placed aboard.

The corpse was dressed in fine clothing and placed on board in a bed. A slave

woman, who had chosen to follow her master in death was sacrificed along with a

horse and a hunting dog. The ship with its contents was burned, and a burial

mound was constructed over the ashes. We have finds of cremated ships graves in

the Nordic countries and in Western European Viking sites, but the large graves

along the Oslofjord were not put to the torch. In the Gokstad ship a man was

found, and the Tune ship probably carried a man a well. How-ever, two women

were buried with the Oseberg ship. The skeletons are of a 50-60 year-old and a

20-30 year-old. We can only speculate as to which was the companion and which

was the noblewoman.

Both the Oseberg and Gokstad graves were plundered by grave robbers, so the

jewelry and luxurious weapons, which surely have been there, were not

excavated. But articles of wood, leather and textiles -- of no interest to the

thieves -- have survived. There are remnants of similar graves in other

locations and it appears to have been standard practice to include sacrificed

dogs and horses, fine weapons, some nautical equip-ment such as oars and a

gangplank, balers, cooking pots for shipmates, a tent and often fine imported

bronze vessels. Without a doubt, these once contained food and drink for the

deceased.

The Oseberg grave contained no trace of weapons, reasonably enough for a

female grave, but all the other standard equipment followed. In addition, the

central figure had been given articles which testify to her dignity as an

administrator and a wife on a wealthy farm. We have to assume that women have

had the main responsibility for carrying out farm work when the men were off on

Viking journeys. The woman from Oseberg was, like many contemporary women, an

authoritative and highly respected lady, whether she sat with other women at a

spinning wheel or loom, or watched over work in the fields, or supervised

milking and the making of cheese and butter. In addition to the ship, she has

brought along a wagon and three sleighs. Both on land and water, she was

prepared to go in style. Enough horses were sacrificed to draw the wagon as

well as the sleighs.

A tent and cooking utensils, tools for textile production, chests and small

boxes for valuables, a breadboard, milk pails and ladles, a cutting knife and

frying pan, shovels and rakes, a saddle, a dog collar and much more was found

in the grave. Her provisions included two slain oxen. A dough of rye flour was

placed to leaven on the large wooden breadboard, and in a finely decorated

bucket, apples were included for dessert.

Many of the wooden articles were ornamentally carved. It appears as if a number

of artists were at work on the farm. Even such utilitarian things as the sleigh

poles are ornately carved. Aside from the Oseberg find, our main knowledge of

Viking art comes from metal jewelry, where the format is modest. The choice of

motif is the same for woodcarving. The artists have been preoccupied with

animal figures. These are imaginary animals, twisted and braided together in a

tight asymmetric arabesque. These carvings are superb examples of advanced

craftsmanship, so the Oseberg wood carvers must have been as handy with chisels

and sheath knives as with swords and battle axes.

The man buried in the Gokstad ship has also had the service of a gifted

woodcarver, even though the find is not so rich in ornamentation as the Oseberg

grave. The Oseberg ship has a low freeboard and is less seaworthy than the

ships from Tune and Gokstad, but it certainly could have managed a North Sea

voyage and could be typical of the ships which were used for the first Viking

attacks around the year 800. A copy which has been built proved to be quick to

the wind, but was not easy to manage. The Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune ships were

probably the private vessels of rich persons, rather than longships for

transporting warriors. The Gokstad ship is very seaworthy. This has been

demonstrated by replicas which have crossed the Atlantic in modern times. The

hull design makes the ship fast -- either under sail or when 32 men pulled on

the oars. Even with a full crew, the Gokstad ship drew no more than one metre

of water, so it could easily have been used for assaults on foreign shores. It

is possible that the Vikings' experiences through frequent sea voyages in the

early 9th Century led to a rapid evolution in hull design. If this is a correct

assumption, then the differences between the Oseberg ship and the Gokstad ship

might be a result of three generations of experience in the North Sea and hours

of discussion between shipbuilders seeking improvements.

1000 years of development

The Viking ships were

clinch-built. The ships used for travelling to distant shores were a result of

a thousand years of experience in the Nordic area. Shipbuilders strove to

construct light-weight and flexible vessels, pliant to the forces of sea and

wind -- working with the elements instead of against them. The hull of the

Viking ships is built on a solid keel, which together with a finely curved bow,

forms the backbone of the vessel. Strafe after strafe was fitted to keel and

stem and these were bolted to each other with iron rivets. This hull shell provided

strength and flexibility. After the shipbuilder had given the shell its desired

shape, ribs made from naturally-curved trees were fitted and these gave

additional strength. To increase flexibility, strafes and ribs were bound

together. Cross supports at the water-line supplied lateral support, and extra

solid logs braced the mast.

The ships sailed were

square-rigged on a midship mast. In a calm, or against a strong headwind, the

crew could man the oars.

As the Viking period

progressed, different types of ships were developed. There were ships intended

for battle which were built for speed and a large crew. There were also ships

built for commercial trade, where speed was less important. These had a greater

girth to permit more cargo. Trade ships did not have a large crew, and they

were better suited for sailing than for rowing.

|

|

http://www.jomsborg.pl/lodz_en.html

Viking Longships.

Look at the map of the Viking

world. How far west had the Vikings travelled? What were the farthest points

they had travelled to the north, east and south?

This passage from Egil's Saga

shows how news travelled throughout the Viking world long before the time of

telephones, radio and television. A Viking called Bjorn wanted to marry a young

woman called Thora, but her father would not give them his permission. So Bjorn

took Thora away. Because of this, Bjorn was declared an outlaw, and this

message was passed from settlement to settlement:

Just before winter a boat from Orkney put in at

Shetland. It brought news that a longship from Norway had arrived at Orkney in

the autumn. The king's men had been aboard, carrying the message that the king

wanted Bjorn dead, no matter where he was found. This same message had been

sent to the Hebrides and even as far as Dublin.

Try

to find all the places mentioned in this story in your atlas.

This extract and others from

Egil's Saga show us that the Vikings were a sea-going people. For them, their

ships were of the greatest importance. They had to be large and strong, able to

travel great distances and survive heavy seas and Atlantic storms. Viking

longships were some of the best sea-going vessels the world has ever seen

Let us try to find out what

these longships were like:

As you read the evidence note

important pieces of information about the ships - what they looked like, how

big they were, how people lived on board, how they moved through the water, how

they were steered.

Here are two lined from

Egil's Saga. How was the ship propelled? What decorated the ship?

Let's beat the oar blades

Of our shield adorned ship.

Another

part of the saga mentions two other Vikings:

They had a fast ship with twelve or thirteen

oars on each side and a crew of about thirteen men.

The ship was richly painted above the sea line and magnificently decorated . .

. and it had a blue and red striped sail . . . It was fully rigged with tents

and provisions.

Great

Viking poems like King Harold's Saga tell us many things about

longships. They are mentioned so often that they must have been of great

importance to their owners.

See the great longship

Proudly lies at anchor.

Above the bow,

THe dragon's golden head

Stands high, overlaid with gold.

One Saturday, King Harold

Had the deck tent hauled down.

And the women proudly watched

The ship speed past.

Battle-keen warriors

Pulled oars through the water.

Norwegian arms heaved

The iron nailed dragon

Down the river

Like an eagle on the wing.

Driving west from Russia

Harold's gold filled ship

Sails wet with spray

Flying before the wind

The colourful sails strain.

This

is a Viking burial ship known as the Oseberg ship. It is in a museum in Oslo. Like many people long ago,

the Vikings sometimes buried valuable things with their dead loved ones. When

Egil's brother died in battle. according to the saga, his weapons, clothing and

gold jewellery were buried along with him.

Some Viking princes were so

rich that they could afford to be buried in their magnificent longships. Some

of these ship burials have been discovered and examined by archaeologists.

Things to do.

Using the written evidence

and the pictures, draw your own picture of a Viking longship.

Look up the meaning of each

of these words or phrases: Prow, stern, keel, rudder, oar port.

Label your longship drawing

to show these parts.

Here is a list of things

found in a ship burial. Write the list in your notebook.

Beside each item tell why you think it was carried on a Viking ship:

- 3 small boats.

- 6 collapsible beds.

- A heap of white cloth, striped with

red.

- A pile of thin, strong rope.

- 2 wooden walls shaped like the end

of a tent.

- 32 iron shields.

Looking at

the evidence.

- Name the

animal and bird which the sagas used to describe the ships.

- Why do you

think these creatures were chosen?

- How did

Vikings shelter themselves and keep warm while sleeping at sea on their

long voyages?

- What do you

think the term iron-shielded ship means?

- Why do you

think that one of the ships described had a dragon's golden head on its

prow.

- What other

decorations were used?