|

Ferdinand

I

|

|

|

|

King of the Romans

|

|

Reign

|

5

January 1531 - 25 July 1564

|

|

Coronation

|

11

January 1531, Aachen

|

|

Predecessor

|

Charles V

|

|

Successor

|

Maximilian II

|

|

Holy Roman Emperor

|

|

Reign

|

1558

- 1564[1]

|

|

Predecessor

|

Charles V

|

|

Successor

|

Maximilian II

|

|

King of Bohemia

|

|

Reign

|

24

October 1526 - 25 July 1564

|

|

Coronation

|

24

February 1527, Prague

|

|

Predecessor

|

Louis II

|

|

Successor

|

Maximilian II

|

|

King of Hungary

|

|

Reign

|

16

December 1526 - 25 July 1564

|

|

Coronation

|

3

November 1527,Székesfehérvár

|

|

Predecessor

|

Louis II

|

|

Successor

|

Maximilian II

|

|

|

|

Spouse

|

Anna of Bohemia and

Hungary

|

|

Issue

|

|

Maximilian II, Holy

Roman Emperor

Elisabeth, Queen of

Poland

Joanna, Grand Duchess

of Tuscany

Anna, Duchess of

Bavaria

Ferdinand II,

Archduke of Austria

Catherine, Queen of

Poland

Barbara, Duchess of

Ferrara

Charles II, Archduke

of Austria

Eleonora, Duchess of

Mantua

|

|

House

|

House of Habsburg

|

|

Father

|

Philip I of Castile

|

|

Mother

|

Joanna of Castile

|

|

Born

|

10

March 1503

Alcala de Henares, Castile,Spain

|

|

Died

|

25

July 1564

Vienna, Austria

|

|

Burial

|

Prague, St. Vitus Cathedral

|

Ferdinand

I (10 March 1503 – 25 July 1564) was a Central European monarch from the House of Habsburg. He wasHoly Roman Emperor from 1558, king of Bohemia and Hungary from 1526.[1] Also king of Croatia, Dalmatia, Slavonia as well as, formally, Serbia, Galicia and Lodomeria,

etc. He ruled the Austrian hereditary

lands of the Habsburgs most of his public life, at the behest of his elder brother, Charles V, Holy Roman

Emperor and King of Spain. Ferdinand was Archduke of Austria from 1521 to 1564. After the death of his

brother–in–law Louis II, Ferdinand ruled as King of Bohemia,Hungary (1526–1564).[1][2] When Charles retired in 1556, Ferdinand became his

de facto successor as Holy Roman Emperor, and de jure in 1558,[1][3] while Spain, the Spanish Empire, Naples, Sicily, Milan, the Netherlands, and Franche-Comté went to Philip, son of Charles.

Ferdinand's

motto was Fiat justitia et

pereat mundus: "Let justice be done, though the

world perish".

Ferdinand

in 1531, the year of his election as King of the Romans

Ferdinand

was born in Alcala de Henares,

40 km from Madrid,

the son of the InfantaJoanna of Castile,

the future Queen of Castile known as Joanna

the Mad, and Habsburg Archduke Philip the Handsome, Duke of Burgundy and future King of Castile, who was

heir to Emperor Maximilian I.

Ferdinand shared his birthday with his maternal grandfather Ferdinand II of Aragon.

Charles

entrusted Ferdinand with the government of the Austrian hereditary lands,

roughly modern-day Austria and Slovenia.

Ferdinand also served as his brother's deputy in the Holy Roman Empire during

his brother's many absences and in 1531 was elected King of the Romans,

making him Charles's designated heir in the Empire. Charles abdicated in 1556

and Ferdinand succeeded him, assuming the title of Emperor elect in 1558.

After

Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent killed

Ferdinand's brother-in-law Louis II,

King of Bohemia and

of Hungary at

the battle of Mohács on

29 August 1526, Ferdinand was elected King of Bohemia in his place.

The Croatian nobles at Cetin unanimously elected Ferdinand I as

their king on 1 January 1527, and confirmed the succession to him and his

heirs.[4] In return for the throne Archduke

Ferdinand at Parliament on Cetin (Croatian: Cetinski Sabor) promised to respect

the historic rights, freedoms, laws and customs the Croats had when united with

the Hungarian kingdom and to defend Croatia fromOttoman invasion.[5]

In

Hungary, Nicolaus Olahus,

secretary of Louis, attached himself to the party of King Ferdinand, but

retained his position with the queen-dowager Mary of Habsburg.

Ferdinand was elected King of Hungary by a rump diet in Pozsony in December 1526. The throne of Hungary became the subject of a dynastic

dispute between Ferdinand and John Zápolya,voivode of Transylvania.

Each was supported by different factions of the nobility in the Hungarian

kingdom; Ferdinand also had the support of Charles V. After defeat by Ferdinand

at the Battle of Tarcal in September 1527 and again in Battle of Szina in March 1528, Zápolya gained the

support of Suleiman.

Ferdinand was able to win control only of western Hungary because Zápolya clung

to the east and the Ottomans to the conquered south. Zápolya's widow, Isabella

Jagiełło, cededRoyal Hungary and Transylvania to Ferdinand in the Treaty of Weissenburg of 1551. In 1554 Ogier Ghiselin de

Busbecqwas sent to Istanbul by Ferdinand to discuss a border

treaty over disputed land with Suleiman.

The

most dangerous moment of Ferdinand's career came in 1529 when he took refuge in

Bohemia from a massive but ultimately unsuccessful assault on his capital by

Suleiman and the Ottoman armies at the Siege of Vienna.

A further Ottoman attack on Vienna was repelled in 1533. In that year

Ferdinand signed a peace treaty with the Ottoman Empire,

splitting the Kingdom of Hungary into a Habsburg sector in the west and John

Zápolya's domain in the east, the latter effectively a vassal state of the

Ottoman Empire.

In

1538, by the Treaty of Nagyvárad,

Ferdinand became Zápolya's successor. He was unable to enforce this agreement

during his lifetime because John II Sigismund

Zápolya, infant son of John Zápolya and Isabella

Jagiełło, was elected King of Hungary in 1540. Zápolya was initially

supported by King Sigismund of Poland,

his mother's father, but in 1543 a treaty was signed between the Habsburgs and

the Polish ruler as a result of which Poland became neutral in the conflict. PrinceSigismund Augustus married Elisabeth of Austria, Ferdinand's

daughter.

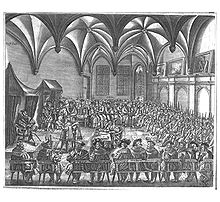

After

decades of religious and political unrest in the German states, Charles V

ordered a general Diet in Augsburg at which the various states would

discuss the religious problem and its solution. Charles himself did not attend,

and delegated authority to his brother, Ferdinand, to "act and

settle" disputes of territory, religion and local power.[6] At the conference, Ferdinand cajoled,

persuaded and threatened the various representatives into agreement on three

important principles. The principle of cuius regio, eius

religio provided

for internal religious unity within a state: The religion of the prince became

the religion of the state and all its inhabitants. Those inhabitants who could

not conform to the prince's religion were allowed to leave, an innovative idea

in the sixteenth century; this principle was discussed at length by the various

delegates, who finally reached agreement on the specifics of its wording after

examining the problem and the proposed solution from every possible angle. The

second principle covered the special status of the ecclesiastical states,

called the ecclesiastical

reservation, or reservatum

ecclesiasticum. If the prelate of an ecclesiastic state changed his

religion, the men and women living in that state did not have to do so.

Instead, the prelate was expected to resign from his post, although this was

not spelled out in the agreement. The third principle, known as Ferdinand's

Declaration, exempted knights and some of the

cities from the requirement of religious uniformity, if the reformed religion

had been practiced there since the mid-1520s, allowing for a few mixed cities

and towns where Catholics and Lutherans had lived together. It also protected

the authority of the princely families, the knights and some of the cities to

determine what religious uniformity meant in their territories. Ferdinand

inserted this at the last minute, on his own authority.[7]

After

1555, the Peace of Augsburg became the legitimating legal document governing

the co-existence of the Lutheran and Catholic faiths in the German lands of the

Holy Roman Empire, and it served to ameliorate many of the tensions between

followers of the so-called Old Faith and the followers of Luther, but it had

two fundamental flaws. First, Ferdinand had rushed the article on ecclesiastical

reservation through

the debate; it had not undergone the scrutiny and discussion that attended the

wide-spread acceptance and support of cuius regio, eius religio.

Consequently, its wording did not cover all, or even most, potential legal

scenarios. The Declaratio

Ferdinandei was

not debated in plenary session at all; using his authority to "act and

settle,"[8] Ferdinand

had added it at the last minute, responding to lobbying by princely families

and knights.[9]

While

these specific failings came back to haunt the Empire in subsequent decades,

perhaps the greatest weakness of the Peace of Augsburg was its failure to take

into account the growing diversity of religious expression emerging in the

so-called evangelical and reformed traditions. Other confessions had acquired

popular, if not legal, legitimacy in the intervening decades and by 1555, the

reforms proposed by Luther were no longer the only possibilities of religious

expression: Anabaptists,

such as the Frisian Menno Simons (1492–1559) and his followers; the

followers of John Calvin,

who were particularly strong in the southwest and the northwest; and the

followers of Huldrych Zwingli were excluded from considerations and

protections under the Peace of Augsburg. According to the Augsburg agreement,

their religious beliefs remained heretical.[10]

In

1556, amid great pomp, and leaning on the shoulder of one of his favorites (the

24-year-old William, Count of

Nassau and Orange),[11] Charles

gave away his lands and his offices. The Spanish empire,

which included Spain,

theNetherlands, Naples, Milan and

Spain's possessions in the Americas,

went to his son, Philip.

His brother, Ferdinand, who had negotiated the treaty in the previous year, was

already in possession of the Austrian lands and was also to succeed Charles as

Holy Roman Emperor.[12] This

course of events had been guaranteed already on January 5, 1531 when Ferdinand

had been elected the King of Romans and so the legitimate successor of the

reigning Emperor.

Charles'

choices were appropriate. Philip was culturally Spanish: he was born in Valladolid and raised in the Spanish court, his

native tongue was Spanish, and he preferred to live in Spain. Ferdinand was

familiar with, and to, the other princes of the Holy Roman Empire. Although he

too had been born in Spain, he had administered his brother's affairs in the

Empire since 1531.[13] Some historians maintain Ferdinand had

also been touched by the reformed philosophies, and was probably the closest

the Holy Roman Empire ever came to a Protestant emperor; he remained nominally

a Catholic throughout his life, although reportedly he refused last rites on

his deathbed.[14] Other historians maintain he was as

Catholic as his brother, but tended to see religion as outside the political

sphere.[15]

Charles'

abdication had far-reaching consequences in imperial diplomatic relations with

France and the Netherlands, particularly in his allotment of the Spanish

kingdom to Philip. In France, the kings and their ministers grew increasingly

uneasy about Habsburg encirclement and sought allies against Habsburg hegemony

from among the border German territories, and even from some of the Protestant

kings. In the Netherlands, Philip's ascension in Spain raised particular

problems; for the sake of harmony, order, and prosperity Charles had not

blocked the Reformation, and had tolerated a high level of local autonomy. An

ardent Catholic and rigidly autocratic prince, Philip pursued an aggressive

political, economic and religious policy toward the Dutch, resulting in a Dutch rebellion shortly after he became king. Philip's

militant response meant the occupation of much of the upper provinces by troops

of, or hired by, Habsburg Spain and the constant ebb and flow of

Spanish men and provisions on the so-called Spanish road from northern Italy, through the Burgundian lands, to and from Flanders.[16]

The

abdication did not automatically make Ferdinand the Holy Roman Emperor. Charles

abdicated as Emperor in January, 1556 in favor of his brother Ferdinand;

however, due to lengthy debate and bureaucratic procedure, the Imperial Diet did not accept the abdication (and

thus make it legally valid) until May 3, 1558. Up to that date, Charles

continued to use the title of Emperor.

Posthumous

engraving of Ferdinand by Martin Rota,

1575

The

western rump of Hungary over which Ferdinand retained dominion became known as Royal Hungary.

As the ruler of Austria, Bohemia and Royal Hungary, Ferdinand adopted a policy

of centralization and, in common with other monarchs of the time, the

construction of an absolute monarchy.

In 1527, soon after ascending the throne, he published a constitution for his

hereditary domains (Hofstaatsordnung) and established Austrian-style

institutions in Pressburg for Hungary, in Prague for Bohemia, and in Breslau for Silesia.

Opposition from the nobles in those realms forced him to concede the

independence of these institutions from supervision by the Austrian government

in Vienna in 1559.

After

Ottoman invasion of Hungary the traditional Hungarian coronation city, Székesfehérvár fell under Turkish occupation. Thus,

in 1536 Hungarian Diet decided than a new place for coronation of the king as

well as a meeting place for the Diet itself would be set in Pressburg.

Ferdinand proposed that Hungarian and Bohemian diets should convene and hold

debates together with Austrian estates, but both ther former refused such a

innovation.

In

1547 the Bohemian Estates rebelled against Ferdinand after he

had ordered the Bohemian army to move against the German Protestants.

After suppressing Prague with the help of his brother Charles V's Spanish forces, he retaliated by limiting the

privileges of Bohemian cities and inserting a new bureaucracy of royal

officials to control urban authorities. Ferdinand was a supporter of the Counter-Reformation and helped lead the Catholic response against what he saw as the

heretical tide of Protestantism. For example, in 1551 he invited the Jesuits to Vienna and in 1556 to Prague.

Finally, in 1561 Ferdinand revived theArchdiocese of Prague,

which had been previously liquidated due to the success of the Protestants.

Ferdinand

died in Vienna and is buried in St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague.

German, Czech, Slovak, Croatian: Ferdinand I.; Hungarian: I. Ferdinánd; Spanish: Fernando I.

On

25 May 1521 in Linz,

Austria, Ferdinand married Anna of Bohemia and

Hungary (1503–1547), daughter of Vladislaus II of

Bohemia and Hungary and his wife Anne de Foix.

They had fifteen children, all but two of whom reached adulthood:

The Renaissance coin

Ferdinand

I has been the main motif for many collector coins and medals, the most recent

one is the famous silver 20 euroRenaissance coin issued

in 12 June 2002. A portrait of Ferdinand I is shown in the reverse of the coin,

while in the obverse a view of the Swiss Gate of the Hofburg Palace can be

seen.

After

ascending the Imperial Throne Ferdinand's full titulature went as follows: Ferdinand,

by the grace of God elected Holy Roman Emperor, forever August, King in

Germany, of Hungary, Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Rama, Serbia,

Galicia, Lodomeria, Cumania and Bulgaria, etc. Prince-Infante in Spain,

Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, Brabant, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola,

Margrave of Moravia, Duke of Luxemburg, the Upper and Lower Silesia,

Württemberg and Teck, Prince of Swabia, Princely Count of Habsburg, Tyrol,

Ferrette, Kyburg, Gorizia, Landgrave of Alsace, Margrave of the Holy Roman

Empire, Enns, Burgau, the Upper and Lower Lusatia, Lord of the Wendish March,

Pordenone and Salins, etc. etc.[17]

Not

always he used all these elements, often omitting few last royal titles (Rama,

Serbia and so forth).

§

Kings of Germany

family tree.

He was related to every other king of Germany.

§

A pedigree of the Habsburg

1.

^ a b c d Britannica 2009

2.

^ http://www.bartleby.com/65/fe/Ferdi1HRE.html

3. ^ "Rapport établi par M. Alet VALERO" (PDF). CENTRE NATIONAL DE DOCUMENTATION

PÉDAGOGIQUE. 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

4.

^ R. W. SETON

-WATSON:The southern Slav question and the Habsburg Monarchy page 18

5.

^ Milan Kruhek: Cetin, grad izbornog sabora Kraljevine

Hrvatske 1527, Karlovačka Županija, 1997, Karlovac

6.

^ Holborn,

p. 241.

7.

^ For a general discussion of the impact of the

Reformation on the Holy Roman Empire, see Holborn, chapters 6–9 (pp. 123–248).

8.

^ Holborn,

p. 241.

9.

^ Holborn,

pp. 244–245.

10. ^ Holborn,

pp. 243–246.

11.

^ Lisa Jardine, The

Awful End of William the Silent: The First Assassination of a Head of State

with A Handgun, London, HarperCollins, 2005, ISBN 0007192576, Chapter 1;

Richard Bruce Wernham, The New

Cambridge Modern History: The Counter Reformation and Price Revolution

1559–1610, (vol. 3), 1979, pp. 338–345.

12. ^ Holborn,

pp. 249–250; Wernham, pp. 338–345.

13. ^ Holborn,

pp. 243–246.

14. ^ See

Parker, pp. 20–50.

15. ^ Holborn,

pp. 250–251.

16. ^ Parker,

p. 35.

17. ^ http://eurulers.angelfire.com/hungary.html

18.

^ Ferdinand used the title of a King of Italy though he

was never crowned as such.

19.

^ Charles had abdicated in 1556, but Ferdinand formally

assumed the title of Emperor elect only in 1558, upon the acceptance of

Charles' abdication.

BioPhotosVos avis

Anthony

Van Dyck (nom anglicisé d’Antoon van Dijk) est le plus célèbre des

collaborateurs et disciples de Pierre-Paul

Rubens. Né à Anvers, il est de 1610 à 1614, alors qu’il est presque

encore enfant, l’assistant en chef du plus grand maître flamand de l’époque,

Rubens, dont l’influence sur le jeune artiste est immense. Van Dyck devient

peintre indépendant dès 1615, à l’âge de seize ans, et en 1618, est membre de

la Guilde de Saint-Luc.

Pourtant, dès 1620, Van Dyck se rend en Angleterre, à l’appel du roi James Ier.

Là, la découverte dans une collection particulière de l’œuvre du Titien agit sur lui comme une révélation. Il

retourne ensuite dans les Flandres, puis voyage en Italie. Il y reste six ans,

principalement à Gênes, de 1621 à 1627, étudie les maîtres italiens de la

Renaissance et y débute une carrière remarquable de portraitiste.

Après un retour à Anvers de plusieurs années, où il obtient de nombreuses

commandes, Van Dyck part pour Londres en 1632, où il est anobli et devient le premier

peintre de la cour. Il réalise de nombreux portraits du roi Charles Ier et de

sa famille, mais aussi de la cour et de sa propre famille. Il met alors au

point un style de portrait alliant, sur fond de paysage, une élégance détendue

et une autorité perceptible, qui fera école en Angleterre jusqu’à la fin du

XVIIIe siècle. La touche fluide est typiquement rubénienne, mais les couleurs

métalliques, l’argenté et le doré, et la transparence des tons lui sont

propres, et vont exercer sur la peinture anglaise, jusqu’à Gainsbourough et

Turner, une influence considérable.

De passage à Paris en 1641, il tombe gravement malade et meurt quelques mois

plus tard à Londres, à l’âge de quarante-deux ans.

Quelques œuvres majeures :

- La

marquise Elena Grimaldi (1623, Washington, National Gallery)

- Autoportrait

au tournesol (1632, collection particulière)

- Charles

Ier (1633, Londres, Buckingham Palace)

- Déposition

de croix (1634, Munich, Alte Pinakothek)

- Charles

Ier, roi d’Angleterre, à la chasse (1635, Paris, musée du Louvre)

- Lord

John et lord Bernard Stuart (1638, Londres, National Gallery, ill.)

Jump

to: navigation, search

"Grimaldi"

redirects here. For other uses, see Grimaldi (disambiguation).

The House of Grimaldi is associated with the history of the Republic of Genoa and of the Principality ofMonaco.

The

Grimaldi family descends from Grimaldo, a Genovese statesman

at the time of the early Crusades. He was the son of Otto Canella, a Consul of

Genoa in 1133, and in turn Grimaldo became a Consul in 1160, 1170 and again in

1184. His numerous grandsons and their children led maritime expeditions

throughout theMediterranean, the Black Sea, and soon the North Sea, and quickly became one of the

most powerful families of Genoa.

The

Grimaldis feared that the head of a rival Genoese family could break the

fragile balance of power in a political coup and become lord of Genoa, as had

happened in other Italian cities. They entered into a Guelphic alliance

with the Fieschi family

and defended their interests with the sword. The Guelfs however were banned

from the City in 1271, and found refuge in their castles of Liguria and

in Provence. They signed a treaty with Charles of Anjou, King of Naples and Count of Provence, to retake control of

Genoa, and generally to provide mutual assistance. In 1276, they accepted a

peace under the auspices of the Pope, which however did not put an end to the

civil war. Not all the Grimaldis chose to return to Genoa, as they preferred to

settle in their fiefdoms, where they could raise armies.

In 1299, the

Grimaldis and their allies launched a few galleys to attack the port of Genoa

before taking refuge on the Western Riviera. During the following years, the

Grimaldis were going to enter into different alliances

that would allow them to come back in force. This time, it was the turn of

their rivals, the Spinola family,

to be banned from the City. During all that period, both Guelfs and Ghibellines took and abandoned the castle of

Monaco, which was ideally located to launch political and military operations

against Genoa. Therefore, the story of Francis Grimaldi and his faction—who conquered the

castle of Monaco under the disguise of friars in 1297—is largely anecdotal.

In the early 14th century, the Catalans from

Spain raided the shores of Provence and Liguria, challenging Genoa and King Robert of Provence. In 1353, the combined

fleet of eighty Venetian and Catalonian galleys gathered

in Sardinia to

meet the fleet of sixty galleys under the command of Anthony Grimaldi. Only

nineteen Genoese vessels survived the battle. Fearing an invasion, Genoa rushed

to request the protection of the lord of Milan.

Several of the

oldest feudal branches of the House of Grimaldi appeared during those unrests,

such as the branches of Antibes, Beuil, Nice, Puget, and Sicily. In 1395, the Grimaldis took

advantage of the discords in Genoa to take possession of Monaco, which they

then ruled as a condominium. It is the origin of today's

principality.

As it was customary in Genoa, the Grimaldis organized

their family ties within a corporation called Albergo. In the political reform of 1528,

this ancient family became one of the 28 alberghi of the Republic of Genoa, to

which other families were formally invited to join. Other Alberghi included the Doria and Pallavicinifamilies. The House of Grimaldi

provided many illustrious personalities such as doges, cardinals, cabinet ministers, and

countless officers. Through an intermarriage with the Serra Family they became

related to the Dukes of Cassano and Gerace.

Until 2002, a treaty between

Monaco and France stated

that if the Grimaldi family ever failed to produce a male heir then the sovereignty over the territory would revert to

France. The 2002 agreement modified this to make provisions for a regency and

continued Monegasque sovereignty if such an event were to occur.

The coat of arms of the House of Grimaldi are simply

described as fusily argent and gules, i.e., a pattern of red diamonds on a

white background.

Elena Grimaldi, as painted by Anthony Van Dyck, c. 1623

Size of this preview: 424 × 600 pixels

Full resolution (1,256 × 1,776

pixels, file size: 262 KB, MIME type: image/jpeg)

The Columbia

Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition | 2008 | Copyright

Sir Anthony Van Dyck , 1599-1641, Flemish portrait and religious painter and

etcher, b. Antwerp. In 1618 he was received as a master in the artists' guild,

but even before this he produced independent paintings in his studio. For a few

years he was the skilled assistant and close collaborator of Rubens . In 1620 he was summoned to England

by James I, whose portrait (now lost) he painted. The next year he went to

Italy, where he studied the works of the great Venetians and painted a series

of portraits of the Genoese nobility. These pictures, many of them still in the

palaces of the Doria, Balbi, Durazzo, and Grimaldi families, show Van Dyck's

extraordinary gift for aristocratic portraiture. Van Dyck conferred upon his

sitters elegance, dignity, and refinement, qualities pleasing to royalty and

aristocracy. An outstanding example is the portrait of Marchesa Elena Grimaldi

(National

...

' alt="Read entire

entry" title="Read entire entry"

v:shapes="_x0000_i1287">

' alt="Read entire

entry" title="Read entire entry"

v:shapes="_x0000_i1287">

Sponsored

Links

Home > Library > History, Politics & Society > World Chronology

1621 1622 1623 1624 1625 1626 1627 1628 1629 1630

political events

England's prince

of Wales travels in secret to Spain with George Villiers, 1st marquess of

Buckingham, who has persuaded him to seek the hand of the infanta Maria, sister

of Felipe IV. "Mr. Smith" and "Mr. Brown" arrive at Madrid

March 7 but find the infanta and Spanish courtunenthusiastic, put off by Buckingham's arrogant manner, anddistrustful of young Charles's promise to change

English penal laws against Catholics (see Great Protestation, 1621). The diminutive (four foot-seven

inch) Charles, now 22, makes the 30-year-old Villiers a duke May 18 (the first

duke created since the execution of Norfolk in 1572), returns October 5, and

will be betrothed instead to the sister of France's

Louis XIII.

The Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II gives the Upper Palatinate to

Maximilian, duke of Bavaria, as the Thirty Years' War continues. Maximilian

makes the duchy an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire, and the Upper Palatinate

will be incorporated into the electorate in 1628. Papal troops occupy the

Valtelline and graf von Tilly advances toWestphalia after defeating Christian of Brunswick

at Stadtlohn.

The Ottoman sultan

Mustapha I abdicates under pressure in favor of his 14-year-old nephew and is

confined in the Seraglio (see 1622). The nephew will reign until 1640

as Murad IV, with his mother, Kösem

Sultana, serving as regent until his majority.

Persia's Abbas I

takes Baghdad, Mosul, and all of Mesopotamia from the Ottoman Turks. Baghdad

will remain in Persian hands for 15 years.

Japan's

shōgun Hidetada Tokugawa abdicates at age 45, having consolidated his

family's rule, eliminated Christianity, and begun the process of closing the

country to outsiders. He is succeeded by his son 19-year-old son Iemitsu, who

will raise the shōgunate to its greatest glory in the next 28 years,

eliminating the emperor's few remaining prerogatives while continuing his

father's campaign against Christians.

Ndongo princess

Nzinga succeeds to the throne after poisoning her brother. Her small monarchy is

dwarfed by the neighboring Portuguese colony of Angola, but she is determined

to resist the depredations of slave traders. She travels to Angola, where she

negotiates with the governor and allows herself to be baptized into

Christianity as Dona Aña de Souza (but see 1624).

Dutch forces seize

the Brazilian port of Pernambuco that will later be called Recife.

exploration, colonization

Another large

group of English colonists arrives at Plymouth.

The port of Gloucester

is founded in the Massachusetts Bay colony.

The Dutch make

Nieuw Nederland a formally organized province and organize a group of families

to settle there (see 1614). The Dutch West India Company

chartered 2 years ago draws up Provisional Regulations for Colonists under

whose terms they are to be provided with clothing and supplies from the

company's storehouses, these to be paid for at modest prices in installments,

but the colonists may not produce any handicrafts and may engage in trade only

if they sell their wares to the company. They must promise to stay for at least

6 years and to settle wherever the company locates them (see 1624).

Sir Thomas Warner

arrives in the Caribbean and establishes the first successful English colony in

the West Indies on the west coast of Saint Christopher, whose name will be

shortened by the colonists to Saint Kitts (see 1632; Columbus, 1493; Bélain, 1627).

commerce

Dutch

governor-general Jan Pieterzsoon Coen leaves for the Netherlands in February,

and Dutch East India Company agents at Amboina proceed promptly to end English East

India Company efforts to trade with the Spice Islands, Japan, or Siam. Believing that the English

merchants plan to kill him with help from Japanese mercenaries and overwhelm

the Dutch garrison as soon as an English ship arrives to support them, Governor

Herman van Speult has ordered the arrest of the alleged conspirators early in

the year. They admit guilt under torture, 10 rival English traders are executed

in February along with 10 Japanese and a Portuguese, and what the English will

call the Amboina Massacre brings to a halt all attempts at Anglo-Dutch

cooperation in the region. Coen is forbidden to return to the Indies pending an

investigation (see 1627), but hereafter it will be the Dutch who control the

East Indies.

English traders in

Japan abandon their commercial station at Hirado (see 1613).

Pilgrim Fathers in

the Plymouth colony assign each family its own parcel of land, forsaking the communal Mayflower Compact of 1620 (see Virginia, 1611). Given new incentive, women and children join with

men to plant corn and increase production.

technology

A new English

patent law protects and encourages inventors.

German

mathematician and astronomer Wilhelm Schickard, 31, writes to his friend

Johannes Kepler September 23 describing his progress in inventing a Rechenmaschiene (computer) (seescience [Oughtred's

slide rule], 1622). A professor at the University of

Tübingen in Württemberg, Schickard has built a mechanical device that employs

six dented wheels geared through a "mutilated" wheel to add and subtract up to six-digit numbers; with every

full turn of this wheel another wheel located to its right rotates 1/10 of a

full turn, an overflow mechanism rings a bell, and a set of

Napier's cylinders in the machine's upper half helps to perform

multiplications, enabling the Rechenmaschiene to multiply as well as add, subtract, and divide.

Schickard and his family will die in an epidemic of bubonic plague in 1635, his detailed notes will not

be discovered until 1935, and their significance will not be recognized for

another 20 years (see Pascal, 1642).

science

Pinax Theatri

Botanici by

Swiss physician, anatomist, and botanist Gaspard Bauhin,

63, introduces a scientific binomial system of classifaction. A compilation

that pulls together uncoordinated plant names and descriptions of some

6,000 species mentioned by Theophrastus and Dioscorides, plus later herbals and

plant records, it represents the first effort to summarize the confusing names (see Linnaeus, 1737).

medicine

Italian anatomist

Gasparo Aselli, 42, performs a vivisection operation on a dog that has just eaten

a substantial meal and discovers "chyle" (lacteal) vessels. Aselli

finds that the dog'speritoneum and intestine are covered with a mass of white

threads (see Pecquet, 1643).

Smallpox is

reported for the first time in Russia, where epidemics of the disease will be

as devastating as they are elsewhere.

religion

Pope Gregory XV

dies at Rome July 8 at age 69 after a 2-year reign in which he has introduced

the secret ballot for papal elections and established the Church's first

permanent board of control of its foreign missionaries (the Congregation for

the Propagation of the Faith). He is succeeded August 6 by Mateo Cardinal

Barberini, 55, who 3 years ago wrote a poem in honor of Galileo Galilei and will reign until 1644 as Urban

VIII.

literature

Nonfiction: Assayer by

Galileo Galilei is a polemic on the philosophy of science. The

astronomer and mathematician dedicates it to the new pope Urban VIII.

Scholar Paolo

Sarpi dies at his native Venice January 14 at age 70.

art

Painting: Portrait

of Cardinal Bentivoglio, Portrait

of François Duquesnoy, and Marchesa

Elena Grimaldi, Wife of Marchese Nicola Cattaneo by Anthony Van Dyck; Baptism of Christ by Guido Reni. Diego Velázquez gains

appointment as court painter at Madrid, where he will be famous for his naturalistic

portraits of Felipe IV, the Infanta Maria, Marianna of Austria, Olivarez, court

jesters, dwarfs, idiots, and beggars in addition to his religious paintings.

Sculpture: David by

Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

theater, film

Theater: Love,

Honor and Power (Amor,

Honor y Poder) by Spanish playwright Pedro Calderón de la Barca, 23; The Duke of Milan by Philip Massinger.

Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories and Tragedies According to

the True Originall Copies(First

Folio) is published at London by the bard's friends John Heminge, 67, and

Henry Condell with 14 comedies, 10 histories, 11 tragedies, and a dedicatory

poem by Ben Jonson "To the memory of my beloved, The Author Mr. William

Shakespeare and what he hath left

us." Heminge (or Heming, or Hemmings) prospered as a member of the King's

Men theatrical company and served as its business manager for more than 25

years.

music

Composer William

Byrd dies at Stondon Massey, Essex, July 4 at age 80. A Roman Catholic, he has

composed music for both the Catholic and Anglican liturgy and has been at

Stondon Massey since 1593.

architecture, real estate

The Paris Church

of St. Marie de la Visitation is completed by architect François Mansart, 25.

agriculture

Brazil has 350

sugar plantations, up from five in 1550.

food availability

The Plymouth

Plantation receives 60 new settlers, who are given lobster and a little fish along with spring

water for lack of anything better to eat and drink (see 1622). The colony has six goats, 50

pigs, and many hens (see 1624).

population

A Spanish edict

offers rewards and special privileges to encourage large families, but the

offer has little effect on birthrates.

1621 1622 1623 1624 1625 1626 1627 1628 1629 1630

·

Sponsored

Links

Top

Home > Library > Science > Science & Technology

Biology

Pinax theatri

botanici by

anatomist Gaspard Bauhin, [b. Basel, Switzerland, January 17, 1560, d. Basel,

December 5, 1624] introduces the practice of using binomial names, one for the genus and a second

for the species. See also 1735 Biology.

Communication

The Statute of

Monopolies, which lays down the laws for granting patents (that is, monopolies

limited to a period of time) for inventions, is passed in England. Previously,

the king had granted monopolies; subsequent efforts through the reign of

Charles I to reassert the king's powers in this matter are

finally and definitely overcome by the Long Parliament in 1640. See also 1474 Communication; 1790 Communication; 1790 Communication.

Computers

In Tübingen

(Germany) astronomer Wilhelm Schickard (Schickardt) [b. Herrenberg (Germany),

April 22, 1592, d. Tübingen, October 23, 1635] builds a mechanical calculator

based on the ideas of Napier's bones. The machine can add, subtract, multiply, and divide and is

intended to aid astronomical calculations. A copy is planned for Kepler, but not completed as a result

of the Thirty Years' War, which also results in the loss of Schickard's

calculator. Discovery of a description in 1957 of the Kepler model leads to

construction of a working copy. See also 1617 Computers; 1957 Computers.

Wiki: Anthony van Dyck (2/2)

This triple portrait of King Charles I was sent to Rome for Bernini to model a bust on

His great success

compelled van Dyck to maintain a large workshop in London, a

studio which was to become "virtually a production line for

portraits". According to a visitor to his studio he usually only made a

drawing on paper, which was then enlarged onto canvas by an assistant; he then

painted the head himself. The clothes were left at the studio and often sent

out to specialists. [21]In

his last years these studio collaborations accounted for some decline in the

quality of work. [27] In

addition many copies untouched by him, or virtually so, were produced by the

workshop, as well as by professional copyists and later painters; the number of

paintings ascribed to him had by the 19th century become huge, as with Rembrandt, Titian and others. However most of his assistants

and copyists could not approach the refinement of his manner, so compared to

many masters consensus among art historians on attributions to him is usually

relatively easy to reach, and museum labelling is now mostly updated (country house attributions may be more dubious in

some cases). The relatively few names of his assistants that are known are

Dutch or Flemish; he probably preferred to use trained Flemings, as no English

equivalent training yet existed.[6] Adriaen Hanneman (1604-71) returned to his native Hague in

1638 to become the leading portraitist there. [28] Van

Dyck's enormous influence of English art does not come from a tradition handed

down through his pupils; in fact it is not possible to document a connection to

his studio for any English painter of any significance. [6]

Most major museum

collections include at least one Van Dyck, but easily the most outstanding

collection is the Royal Collection, which still contains many of his paintings

of the Royal Family. The National Gallery, London (fourteen works), The Museo del Prado (Spain) (twenty five works), The Louvre in Paris(eighteen works), The Alte Pinakothek in Munich, The National Gallery of Artin Washington DC and the Frick Collection have splendid examples of all phases

of his portrait style.

Tate Britain held the exhibition Van Dyck & Britain in 2009. [29]

'

v:shapes="_x0000_i1437">"Self Portrait", ca. 1621 Alte Pinakothek

'

v:shapes="_x0000_i1437">"Self Portrait", ca. 1621 Alte Pinakothek

'

v:shapes="_x0000_i1438"> Elena Grimaldi, Genoa 1623

'

v:shapes="_x0000_i1438"> Elena Grimaldi, Genoa 1623

Marie-Louise de Tassis,

Antwerp 1630

Marie-Louise de Tassis,

Antwerp 1630

Queen Henrietta Maria, London 1632

Queen Henrietta Maria, London 1632

v:shapes="_x0000_i1441">Charles

I with M. de St Antoine (1633)

v:shapes="_x0000_i1441">Charles

I with M. de St Antoine (1633)

James

Stuart, Duke of Richmond, ca. 1637

James

Stuart, Duke of Richmond, ca. 1637

Amor

and Psyche, 1638

Amor

and Psyche, 1638

George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol, ca.

1638-9

George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol, ca.

1638-9

1.

So Ellis Waterhouse (as refs below). But Levey (refs

below) suggests that either van Dyck is the sun to which the sun-flower (of

popular acclaim?) turns its face, or that it is the face of the King, on the

medal he holds, as presented by van Dyck to the world

2.

Originally "van Dijck", with the "IJ" digraph, in Dutch. Anthony

is the English for the Dutch Anthonis or Antoon, though Anthonie, Antonio or

Anthonio was also used; in French he is often Antoine, in Italian Anthonio or

Antonio. In English a capitalised "Van" in Van Dyck was more usual

until recent decades (used by Waterhouse for example), and Dyke was often used

during his lifetime and later

3.

Brown, Christopher: Van

Dyck 1599-1641, page 15. Royal Academy Publications, 1999. ISBN 0 900946 66 0

4.

Gregory Martin, The Flemish School, 1600-1900,

National Gallery Catalogues, p.26, 1970, National Gallery, London, ISBN 0901791024

5.

Brown, page 17.

6.

^ Ellis

Waterhouse, "Painting in Britain, 1530-1790", 4th Edn, 1978,pp 70-77, Penguin Books (now Yale History of Art series)

7.

^ Martin, op and

page cit.

8.

Brown, page 19.

9.

Michael Levey, Painting at Court, Weidenfeld

and Nicholson, London, 1971, pp 124-5

10. DNB accessed

may 14 2007

11. DNB ret

3 May 2007 (causeway, and Eltham)

12. Gaunt, William, English Court Painting

13. Levey p 128

14. DNB ret.

3 May 2007

15. ^ (Polish) "Portret królewicza". Treasures....http://swiadectwotestimony.republika.pl/dyck_vasas.html.

Retrieved 2008-08-29.

16. (Polish) "Jan II Kazimierz Waza". www.stat.gov.pl.

www.poczet.com.http://www.poczet.com/janii.htm.

Retrieved 2008-08-29.

17. now in the Accademia Nazionale di San Luca

18. Grove Art Online,

accessed 13 May 2007, DNB 14

May 2007

19. Brown, page 33. In

1666 the Great Fire of London destroyed Old St. Paul's Cathedral,

and with it van Dyck's tomb.

20. Levey, op cit p.136

21. ^ DNB accessed

14 May 2007

22. Martin Royalton-Kisch, The Light of Nature, Landscape

Drawings and Watercolours by Van Dyck and his contemporaries, British

Museum Press, 1999, ISBN0714126217

23. ^ A History of

Engraving and Etching, Arthur M. Hind,p. 165, Houghton

Mifflin Co. 1923 (in USA), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963 ISBN 0486209547

24. DP Becker in KL

Spangeberg (ed), Six Centuries of Master Prints, Cincinnati Art Museum, 1993,

no 72,ISBN 0931537150

25. DP Becker in KL

Spangeberg (ed), Six Centuries of Master Prints, Cincinnati Art Museum, 1993,

no 72,ISBN 0931537150

26. A Hyatt Mayor,

Prints and People, Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, no.433-35, ISBN 0691003262

27. Brown, page 84-6.

28. Rudi Ekkart and

Quentin Buvelot (eds), Dutch

Portraits, The Age of Rembrandt and Frans Hals, Mauritshuis/National

Gallery/Waanders Publishers, Zwolle, p.138 QB, 2007,ISBN 9781857093629

29. Karen Hearn (ed.), Van Dyck & Britain, Tate Publishing, 2009. ISBN 978-1-85437-795-1.

Carlos I

Rei da Inglaterra, da Irlanda e da Escócia

Carlos I retratado

por Anthony van Dyck em 1636

Reinado

24 de março de 1625 –30 de janeiro de 1649

Coroação

2 de fevereiro de 1626

Títulos

Duque de Albany e Duque de York, Príncipe de Gales

Nascimento

19 de novembro de 1600

Dunfermline, Escócia

Morte

30 de janeiro de 1649

Whitehall, Londres

Antecessor

Jaime I

Sucessor

Carlos II (de jure)

Oliver Cromwell, de facto

Consorte

Henriqueta Maria da França

Filhos

Carlos II

Jaime II

Maria Stuart

Elizabeth Stuart

Henrique Stuart, Duque de Gloucester

Henriqueta Ana Stuart

Dinastia

Stuart

Pai

James I

Mãe

Ana de Dinamarca

Carlos I de Inglaterra (em inglês: Charles I; 19 de Novembro de 1600 – 30 de Janeiro de 1649) foi rei da Inglaterra, da Escócia e da Irlandadesde 27 de Março de 1625, até à

sua morte. A sua luta pelo poder travada contra o Parlamento da Inglaterra tornou-se famosa. Como ele era um

defensor do direito divino dos reis, seus inimigos, no parlamento dissolvido

por ele em 1628 e mais tarde nos que foi forçado a reunir em 1640, temeram que

ele procurasse obter o o poder absoluto. Houve uma oposição generalizada a

muitas de suas acções, especialmente a imposição de impostos sem o

consentimento do parlamento.

Primeiros anos | Início do reinado | "Reinado Pessoal": "Onze Anos de

Tirania" | Política religiosa | O "Parlamento Curto" e o "Parlamento

Longo" | Guerra civil | Execução de Carlos I | Na cultura popular | Bibliografia

Anthony van Dyck (many

variant spellings;[2] 22 March 1599 – 9 December 1641) was

a Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England. He is most famous for his

portraits of King Charles I of England and Scotland and his family and court, painted with

a relaxed elegance that was to be thedominant influence on English portrait-painting for the next 150 years. He also

painted biblical and mythological subjects, displayed outstanding

facility as a draftsman, and was an important innovator in watercolour and etching.

Self-portrait,

1613-14.

Van Dyck was born to prosperous parents in Antwerp. His talent was evident very

early, and he was studying painting withHendrick van Balen by 1609, and became an independent

painter around 1615, setting up a workshop with his even younger friendJan Brueghel the Younger.[3] By the age of fifteen he was already a

highly accomplished artist, as his Self-portrait,

1613-14, shows.[citation needed] He was admitted to the Antwerp

painters'Guild of Saint Luke as a free master by February 1618.[4] Within a few years he was to be the

chief assistant to the dominant master of Antwerp, and

the whole of Northern Europe, Peter Paul Rubens, who made much use of

sub-contracted artists as well as his own large workshop. His influence on the

young artist was immense; Rubens referred to the nineteen-year-old van Dyck as

'the best of my pupils'.[5] The origins and exact nature of their

relationship are unclear; it has been speculated that Van Dyck was a pupil of

Rubens from about 1613, as even his early work shows little trace of van

Balen's style, but there is no clear evidence for this.[6] At the same time the dominance of

Rubens in the small and declining city of Antwerp probably explains why,

despite his periodic returns to the city, van Dyck spent most of his career

abroad..[6] In 1620, in the Rubens' contract for

the major commission for the ceiling of the Jesuit church at Antwerp (now destroyed), van

Dyck is specified as one of the "discipelen" who was to execute the

paintings to Rubens' designs.[7]

In 1620, at the instigation of the brother of the Duke of Buckingham, van Dyck went to

England for the first time where he worked for King James I and James VI, receiving £100. [6] It was in London in the collection of Earl of Arundel that he first saw the work of Titian, whose use of colour and subtle

modeling of form would prove transformational, offering a new stylistic

language that would enrich the compositional lessons learned from Rubens.[8]

Genoan hauteur

from the Lomelli family, 1623

After about four months he returned to Flanders, but moved on in late

1621 toItaly, where he remained for 6 years,

studying the Italian masters and beginning his career as a successful

portraitist. He was already presenting himself as a figure of consequence,

annoying the rather bohemian Northern artist's colony in Rome, says Bellori, by appearing with "the

pomp ofXeuxis... his behaviour was that of a

nobleman rather than an ordinary person, and he shone in rich garments; since

he was accustomed in the circle of Rubens to noblemen, and being naturally of

elevated mind, and anxious to make himself distinguished, he therefore wore -

as well as silks - a hat with feathers and brooches, gold chains across his

chest, and was accompanied by servants." [9]

He was mostly

based in Genoa, although he also travelled

extensively to other cities, and stayed for some time in Palermo in Sicily. For the Genoese aristocracy,

then in a final flush of prosperity, he developed a full-length portrait style,

drawing on Veronese and Titian as well as Rubens' style

from his own period in Genoa, where extremely tall but graceful figures look

down on the viewer with great hauteur. In 1627, he went back to Antwerp where

he remained for five years, painting more affable portraits which still made

hisFlemish patrons look as stylish as possible. A

life-size group portrait of twenty-four City Councillors of Brussels he painted for the council-chamber was

destroyed in 1695.[10]. He was evidently very

charming to his patrons, and, like Rubens, well able to mix in aristocratic and

court circles, which added to his ability to obtain commissions. By 1630 he was

described as the court painter of the Habsburg Governor of Flanders, the

Archduchess Isabella. In this period he also produced many religious works,

including large altarpieces, and began his printmaking

(see below).

The more intimate, but still elegant style he developed in England, ca

1638

King Charles I was the most passionate and generous collector of art

among the British monarchs, and saw art as a way of promoting his grandiose

view of the monarchy. In 1628 he bought the fabulous collection that the Gonzagasof Mantua were forced to dispose of, and he had

been trying since his accession in 1625 to bring leading foreign painters to

England. In 1626 he was able to persuade Orazio Gentileschi to settle in England, later to be

joined by his daughter Artemesia and some of his sons. Rubens was an

especial target, who eventually came on a diplomatic

mission, which included painting, in 1630, and later supplied more paintings

from Antwerp. He was very well treated during his nine month visit, during

which he was knighted. Charles' court portraitist Daniel Mytens, was a somewhat

pedestrian Fleming. Charles was extremely short (less than five foot tall) and

presented challenges to a portraitist.

Van Dyck had remained

in touch with the English court, and had helped King Charles' agents in their

search for pictures. He had also sent back some of his own works, including a

portrait (1623) of himself with Endymion Porter, one of Charles's

agents, a mythology (Rinaldo and Armida, 1629, now in theBaltimore Museum of Art), and a

religious work for the Queen. He had also painted Charles's sister, Queen Elizabeth of Bohemia in the Hague in 1632. In April that year, van Dyck

returned to London, and was taken under the wing of the court immediately,

being knighted in July and at the same time receiving a pension of £200 per

year, in the grant of which he was described as principalle Paynter in ordinary to their majesties.

He was well paid for paintings in addition to this, at least in theory, as King

Charles did not actually pay over his pension for five years, and reduced the

price of many paintings. He was provided with a house on the river at Blackfriars, then just outside the City and

hence avoiding the monopoly of the Painters Guild. A suite of rooms in Eltham Palace, no longer used by the

Royal family, was also provided as a country retreat. His

Blackfriars studio was frequently visited by the King and Queen (later a

special causeway was built to ease their access), who hardly sat for another

painter whilst van Dyck lived.[6] [11]

King Charles I,

ca. 1635 Louvre - see text

He was an immediate success in England, rapidly painting a large number

of portraits of the King and Queen Henrietta Maria, as well as their

children. Many portraits were done in several versions, to be sent as

diplomatic gifts or given to supporters of the increasingly embattled king.

Altogether van Dyck has been estimated to have painted forty portraits of King

Charles himself, as well as about thirty of the Queen, nine of Earl of Strafford and multiple ones of other courtiers. [12] He painted many of the court, and also

himself and his mistress, Margaret Lemon. In England he developed a version of

his style which combined a relaxed elegance and ease with an understated

authority in his subjects which was to dominate English portrait-painting to

the end of the 18th century. Many of these portraits have a

lush landscape background. His portraits of Charles on horseback updated the

grandeur of Titian's Emperor Charles V, but even more effective and original is

his portrait of Charles dismounted in the Louvre: "Charles is given a

totally natural look of instinctive sovereignty, in a deliberately informal

setting where he strolls so negligently that that he seems at first glance

nature's gentleman rather than England's King" [13] Although his portraits have created

the classic idea of "Cavalier" style and dress, in fact

a majority of his most important patrons in the nobility, such as Lord Wharton and the Earls of Bedford, Northumberland and Pembroke, took theParliamentarian side in the English Civil War that broke out soon after his death.[14]

Van Dyck became a

"denizen", effectively a citizen, in 1638 and married Mary, the

daughter of Lord Ruthven and a Lady in waiting to the Queen, in 1639-40; this may

have been instigated by the King in an attempt to keep him in England.[6] He had spent most of 1634 in Antwerp,

returning the following year, and in 1640-41, as the Civil War loomed, spent

several months in Flanders and France. In 1640 he accompanied prince John Casimir of Poland after he was freed from French

imprisonment;[15][16] he also painted the prince's portrait. [15][17] He left again in the summer of 1641,

but fell seriously ill inParis and

returned hurriedly to London, where he died soon after in his house at

Blackfriars.[7] He left a daughter each by his wife

and mistress, the first only ten days old. Both were provided for, and both

ended up living in Flanders.[18]

He was buried in Old St. Paul's Cathedral, where the

king erected a monument in his memory:

Anthony returned to England, and shortly afterwards he

died in London, piously rendering his spirit to God as a good Catholic, in the

year 1641. He was buried in St. Paul's, to the sadness of the king and court

and the universal grief of lovers of painting. For all the riches he had

acquired, Anthony van Dyck left little property, having spent everything on

living magnificently, more like a prince than a painter.[19]

Samson and Delilah,

ca. 1630. A strenuous history painting in the manner of Rubens; the saturated

use of color reveals van Dyck's study ofTitian.

With the partial

exception of Holbein, van Dyck and his exact

contemporary Velázquez were the first painters of pre-eminent talent to work

mainly as Court portraitists. The slightly younger Rembrandt was also to work mainly as a

portraitist for a period. In the contemporary theory of the Hierarchy of genres portrait-painting came well belowHistory painting (which covered religious scenes also),

and for most major painters portraits were a relatively small part of their

output, in terms of the time spent on them (being small, they might be numerous

in absolute terms). Rubens for example mostly painted portraits only of his

immediate circle, but though he worked for most of the courts of Europe, he

avoided exclusive attachment to any of them.

A variety of factors meant that in the 17th century demand

for portraits was stronger than for other types of work. Van Dyck tried to

persuade Charles to commission him to do a large-scale series of works on the

history of the Order of the Garter for the Banqueting House, Whitehall, for which

Rubens had earlier done the huge ceiling paintings (sending them from Antwerp).

Henrietta Maria and the dwarf, Sir Jeffrey Hudson, 1633

A sketch for one wall remains, but by 1638 Charles was too

short of money to proceed.[6] This was a problem Velázquez did not have,

but equally van Dyck's daily life was not encumbered by trivial court duties as

Velázquez's was. In his visits to Paris in his last years van Dyck tried to

obtain the commission to paint the Grande

Gallerie of the Louvre without success.[20]

A list of history paintings

produced by van Dyck in England survives, by Bellori, based on information by Sir Kenelm Digby; none of these still

appear to survive, although the Eros

and Psyche done for the King

(below) does.[6] But many other works, rather more

religious than mythological, do survive, and though they are very fine, they do

not reach the heights of Velázquez's history paintings. Earlier ones remain

very much within the style of Rubens, although some of his Sicilian works are

interestingly individual.

Van Dyck's portraits

certainly flattered more than Velázquez's; when Sophia, later Electoress of

Hanover, first met Queen Henrietta Maria, in exile in Holland in 1641, she

wrote: "Van Dyck's handsome portraits had given me so fine an idea of the

beauty of all English ladies, that I was surprised to find that the Queen, who

looked so fine in painting, was a small woman raised up on her chair, with long

skinny arms and teeth like defence works projecting from her mouth..." [6] Some critics have blamed van Dyck for

diverting a nascent tougher English portrait tradition, of painters such asWilliam Dobson, Robert Walker and Issac Fuller into what certainly became elegant

blandness in the hands of many of van Dyck's successors, like Lelyor Kneller.[6] The conventional view has always been

more favourable: "When Van Dyck came hither he brought Face-Painting to us;

ever since which time … England has excel'd all the World in that great

Branch of the Art’ (Jonathan Richardson: An

Essay on the Theory of Painting, 1715, 41). Thomas Gainsborough is reported to have said on his

deathbed "We are all going to heaven, and Van Dyck is of the

Company."[21]

A fairly small

number of landscape pen and wash drawings or watercolours made in England played an important

part in introducing the Flemish watercolour landscape tradition to England.

Some are studies, which reappear in the background of paintings, but many are

signed and dated and were probably regarded as finished works to be given as

presents. Several of the most detailed are of Rye, a port for ships to the Continent,

suggesting that van Dyck did them casually whilst waiting for wind or tide to

improve.[22]

Probably during his period in Antwerp after his

return from Italy, van Dyck began his Iconography,

eventually a very large series of prints with half-length portraits of eminent contemporaries.

Van Dyck produced drawings, and for eighteen of the portraits he himself etched with great brilliance the heads and

the main outlines of the figure, for an engraver to work up: "Portrait etching had

scarcely had an existence before his time, and in his work it suddenly appears

at the highest point ever reached in the art"[23]

Pieter Brueghel the Younger from theIconography; etching by

Van Dyck (only)

However for most of the series he left the whole printmaking work to specialists, who mostly

engraved everything after his drawings. His own etched plates appear not to

have been published commercially until after his death, and early states are

very rare.[24] Most of his plates were printed after

only his work had been done; some exist in further states after engraving had been added,

sometimes obscuring his etching. He continued to add to the series until at

least his departure for England, and presumably added Inigo Jones whilst in London.

The series was a great success, but was his only venture into printmaking;

portraiture probably paid better, and he was constantly in demand. At his death

there were eighty plates by others, of which fifty-two were of artists, as well

as his own eighteen. The plates were bought by a publisher; with the plates

reworked periodically as they wore out they continued to be printed for

centuries, and the series added to, so that it reached over two hundred

portraits by the late 18th century. In 1851 the plates were bought by theCalcographie

du Louvre.[25]

The Iconography was highly influential as a commercial

model for reproductive printmaking; now forgotten series of portrait prints

were enormously popular until the advent of photography:"the importance of

this series was enormous, and it provided a repertory of images that were

plundered by portrait painters throughout Europe over the next couple of centuries."[21] Van Dyck's brilliant etching style,

which depended on open lines and dots, was in marked contrast to that of the other

great portraitist in prints of the period, Rembrandt, and had little influence

until the 19th century, when it had a great influence on artists such as Whistlerin the last major phase of

portrait etching. [23] Hyatt Mayor wrote: "Etchers have studied Van

Dyck ever since, for they can hope to approximate his brilliant directness,

whereas nobody can hope to approach the complexity of Rembrandt's

portraits"[26]

This triple

portrait of King Charles I was sent to Rome for Bernini to model a bust on

His great success

compelled van Dyck to maintain a large workshop in London, a

studio which was to become "virtually a production line for

portraits". According to a visitor to his studio he usually only made a

drawing on paper, which was then enlarged onto canvas by an assistant; he then

painted the head himself. The clothes were left at the studio and often sent

out to specialists.[21] In his last years these studio

collaborations accounted for some decline in the quality of work.[27] In addition many copies untouched by

him, or virtually so, were produced by the workshop, as well as by professional

copyists and later painters; the number of paintings ascribed to him had by the

19th century become huge, as with Rembrandt, Titian and others. However most of his

assistants and copyists could not approach the refinement of his manner, so

compared to many masters consensus among art historians on attributions to him is usually

relatively easy to reach, and museum labelling is now mostly updated (country house attributions may be more dubious in

some cases). The relatively few names of his assistants that are known are

Dutch or Flemish; he probably preferred to use trained Flemings, as no English

equivalent training yet existed.[6] Adriaen Hanneman (1604-71) returned to his native Hague in

1638 to become the leading portraitist there.[28] Van Dyck's enormous influence of

English art does not come from a tradition handed down through his pupils; in

fact it is not possible to document a connection to his studio for any English

painter of any significance.[6]

§

Van Dyck painted many portraits of

men, notably Charles I and himself, with the short, pointed beards then in

fashion; consequently this particular kind of beard was much later (probably

first in America in the 19th century) named a vandykeor Van dyke beard (which is the anglicized version of

his name).

§

During the reign

of George III, a generic

"Cavalier" fancy-dress costume called a Van Dyke was popular;Gainsborough's 'Blue Boy' is wearing

such a Van Dyke outfit.

§

The oil paint pigment van

Dyck brown is named after

him, and Van dyke brown is an early photographic printing

process using the same colour.

§

See also several people and places under Van Dyke, the more common form in

English of the same original name.

Most major museum collections include at least one

Van Dyck, but easily the most outstanding collection is the Royal Collection,

which still contains many of his paintings of the Royal Family. The National Gallery, London (fourteen works), TheMuseo del Prado (Spain) (twenty five works), The Louvre in Paris (eighteen

works), The Alte Pinakothek in Munich, TheNational Gallery of Art in Washington DC and the Frick Collection have splendid examples of all phases

of his portrait style.

Tate Britain held the exhibition Van Dyck & Britain in 2009.[29]

Ernst Gombrich nous apprend que Anton Van Dyck (1599 - 1641) devint le peintre de la

cour de Charles Ier sous le nom anglicisé de Sir Anthony Vandyke et fit le

portrait d'une bonne partie de la noblesse proche du roi. Il avait d'ailleurs

tellement de commandes qu'il se faisait aider par des aides qui peignaient les

costumes des modèles disposés sur des mannequins, le maître se contentant

de peindre les visages ou apporter une simple touche finale.

Le portrait de Charles Ier, roi d'Angleterre dit portrait du

roi à la chasse (que Van Dyck n'a sans doute pas laissé à ses assistants pour

cette fois !) représente le souverain au retour d'une partie de chasse "tel sans doute

qu'il désirait être vu par la postérité : un prince d'une élégance hors pair,

d'une culture raffinée, protecteur des arts, détenteur du pouvoir royal de

droit divin" (E. Gombrich).

Ce portrait payé par Charles Ier n'est pas resté

en Angleterre, le tableau a été transporté en France et acheté par Louis XVI en

1775. L'acquisition

de ce tableau par Louis XVI est un raccourci saisissant car Charles Ier,

partisan d’un pouvoir absolu, voulut imposer à son pays la religion anglicane

et la monarchie de droit divin. Après plusieurs années d'affrontement avec les

parlementaires il fut confronté à une guerre civile et victime de la

première révolution anglaise. Vaincu par Olivier Cromwell et capturé il fut condamné à mort et

décapité (à la hache) en janvier 1649.

Cet évènement est d'ailleurs raconté par Alexandre Dumas

dans "Vingt Ans après" la suite qu'il donna aux "Trois

Mousquetaires". L'action se déroule à l'époque de la Fronde, entre 1648 et

1649. Les quatre héros ont vieilli et sont d'abord séparés par leurs idées

politiques: Athos et Aramis sont du côté des Princes, d'Artagnan et Porthos du

côté de Mazarin. Mais ils finissent par se réunir pour venir en aide à Charles

Ier d'Angleterre. Dans le chapitre intitulé "Remember", Dumas raconte

l'exécution du roi il imagine que les quatre amis, qui n'ont pu sauver le roi,

réussissent, à s'introduire sur le lieu de l'exécution, Athos s'étant glissé

sous l'échafaud.

"Alors Charles s'agenouilla, fit le signe

de la croix, approcha sa bouche des planches comme s'il eut voulu baiser la

plateforme; puis s'appuyant d'une main sur la plancher et de l'autre sur la billot :

- Comte de la Fère, dit il en français, êtes

vous là et puis je vous parler ?

Cette voix frappa droit au coeur d'Athos et le

perça comme un fer glacé.

- Oui Majesté, dit il en tremblant.

- Ami fidèle, coeur généreux, dit le roi, je

n'ai pu être sauvé, je ne devais pas l'être."

Toujours à propos de ce roi j'ai trouvé ce

tableau au Département des objets d'art : "Charles Ier recevant une rose

des mains d'une jeune fille, au moment où il est conduit prisonnier au château

de Carisbrook, pour être bientôt condamné et exécuté" peint par Eugène

Lami en 1829 dans la veine historique et romantique du début du XIXe siècle.

Portrait De Marie

Louise. Fille De François Ier, Empereur D'autriche. Biographie

Carte Postale Marie Louise

Mais, si je devais distinguer une œuvre de Van Dyck, ce

serait probablement le portrait deMarie-Louise de Tassis : une splendeur ! ...

louvre-passion.over-blog.com/article-7024576-6.html - En cache - Pages similaires -

- [ Traduire cette page ]

The painting

'Portrait of Marie-Louise de Tassis'

from Anthonis van Dyck is available as hand painted oil painting, Art print on

canvas and as poster ...

www.wooop.com/app?service=external/...sp...

- États-Unis - En cache -

De même, Van Dyck évoque la douleur de la Vierge Marie avec

une plus grande .... Alors qu'il se préparait à déménager,

il apprit que Louis XIII était sur le ...

users.skynet.be/pierre.bachy/van_dyck.html - En cache -

Marie louise fille empereur d'autriche. Carte raviel

empereur des fantasmes. Interpretation du portrait de marie louise de tassis ...

www.priceminister.com/.../Carte-Postale-Marie-Louise-Portrait-De-Marie-Louise-Fille-De-Francois-Ier-Empereur-D-a...

- En cache - Pages similaires -

- [ Traduire cette page ]

Marie-Louise

de Tassis, Antwerp 1630. Queen Henrietta Maria, London 1632.

Charles I with M. de St Antoine (1633). James Stuart, Duke of Richmond, ca.

1637 ...

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_van_Dyck

- En cache - Pages similaires -

- [ Traduire cette page ]

Download

Portrait of Marie-Louise de Tassis as wallpapers and desktop backgrounds

available in all screen resolutions.

www.art-wallpaper.com/.../Portrait+of+Marie-Louise+de+Tassis - En cache -

Portrait de Marie-Louise de Tassis.

Autoportrait. Charles Ier, roi d'Angleterre. La Famille Lomellini. Marguerite

de Lorraine ...

fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antoine_van_Dyck - En cache - Pages similaires -

- [ Traduire cette page ]

Marie-Louise

de Tassis of Sir

Anthonis van Dyck fine art prints on canvas.

www.my-art-prints.co.uk/.../Marie-Louise-de-Tassis-5736.html

- En cache -

- [ Traduire cette page ]

Portrait of Marie-louise de Tassis after Anthony Van Dyck. Written on

July 22, 2008. My second Van Dyck piece went in a very different direction

after ...

baroquenheart.com/?p=19 - En cache -

![]()

![]() ' alt="Read entire

entry" title="Read entire entry"

v:shapes="_x0000_i1287">

' alt="Read entire

entry" title="Read entire entry"

v:shapes="_x0000_i1287">

'

v:shapes="_x0000_i1437">"Self Portrait", ca. 1621 Alte Pinakothek

'

v:shapes="_x0000_i1437">"Self Portrait", ca. 1621 Alte Pinakothek

'

v:shapes="_x0000_i1438"> Elena Grimaldi, Genoa 1623

'

v:shapes="_x0000_i1438"> Elena Grimaldi, Genoa 1623 Marie-Louise de Tassis,

Antwerp 1630

Marie-Louise de Tassis,

Antwerp 1630 Queen Henrietta Maria, London 1632

Queen Henrietta Maria, London 1632

v:shapes="_x0000_i1441">Charles

I with M. de St Antoine (1633)

v:shapes="_x0000_i1441">Charles

I with M. de St Antoine (1633) James

Stuart, Duke of Richmond, ca. 1637

James

Stuart, Duke of Richmond, ca. 1637 George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol, ca.

1638-9

George Digby, 2nd Earl of Bristol, ca.

1638-9![]()