OW RESOLUTION (HVR1)

MATCHES

|

|

|||||

|

Country |

Your Matches |

Comment |

Match Total |

Country Total |

Percentage |

|

England |

13 |

- |

13 |

6 348 |

0,2% |

|

France |

3 |

- |

3 |

2 286 |

0,1% |

|

Germany |

12 |

- |

12 |

7 176 |

0,2% |

|

Ireland |

7 |

- |

7 |

5 555 |

0,1% |

|

Italy |

1 |

- |

1 |

2 365 |

< 0.1% |

|

Netherlands |

1 |

- |

1 |

890 |

0,1% |

|

Poland |

3 |

- |

3 |

2 671 |

0,1% |

|

Scotland |

11 |

- |

11 |

2 678 |

0,4% |

|

South Africa |

1 |

- |

1 |

145 |

0,7% |

|

Sweden |

1 |

- |

1 |

1 271 |

0,1% |

|

United Kingdom |

5 |

- |

6 |

5 010 |

0,1% |

|

1 |

British Isles |

||||

|

Wales |

2 |

- |

2 |

606 |

0,3% |

OW

RESOLUTION (HVR1)

|

Haplo |

Country |

Comment |

Match Total |

|

H |

England |

- |

11 |

|

H |

France |

- |

2 |

|

H |

Germany |

- |

11 |

|

H |

Ireland |

- |

5 |

|

H |

Italy |

- |

1 |

|

H |

Poland |

- |

2 |

|

H |

Scotland |

- |

7 |

|

H |

South Africa |

- |

1 |

|

H |

Sweden |

- |

1 |

|

H |

United Kingdom |

- |

4 |

|

H2a2 |

England |

- |

2 |

|

H2a2 |

Ireland |

- |

1 |

|

H2a2 |

Poland |

- |

1 |

|

H2a2 |

Scotland |

- |

1 |

|

H2a2b1 |

France |

- |

1 |

|

H2a2b1 |

Germany |

- |

1 |

|

H2a2b1 |

Ireland |

- |

1 |

|

H2a2b1 |

Netherlands |

- |

1 |

|

H2a2b1 |

Scotland |

- |

3 |

|

H2a2b1 |

United

Kingdom |

- |

1 |

|

H2a2b1 |

United

Kingdom |

British Isles |

1 |

|

H2a2b1 |

Wales |

- |

2 |

HIGH

RESOLUTION (HVR1+HVR2)

|

No matches found. |

Votre haplogroupe

et les mutations par rapport à la séquence de référence CRS sont affichés

ci-après. Une valeur de la CRS indique qu'il n'y a pas de mutation. Des

résultats de la région HVR2 (test de haute résolution) s'affichent uniquement

si vous avez demandé un test de précision (mtDNAPlus / mtDNA Refine test). Si

vous avez commandé un test complet de votre ADNmt (Mega mtDNA), la région

codante s'affichera ci-après.

Afin de mieux comprendre les résultats de vos tests

d'ADNmt, il vous est recommandé de lire le didacticiel des

résultats d'ADNmtque nous avons

conçu sous forme de foire aux questions relative aux résultats d'ADNmt.

Haplogroupe - H2a2b1

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Anton VanDyck WANCLIK 1599 |

Earl of Bristol 1638 |

Franziskus WANCLIK 1870 |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

George Digby 2nd Earl of Bristol ca 1638-39 |

Anton Vandike WANCLIK |

|

||||||

|

|

|

||||||

Ancient Western Eurasian DNA

In tracing relationships through

genetics, researchers have focused on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is

passed from mother to child, and Y-DNA, which is passed from father to son. The

pioneer studies of ancient DNA mainly tested only a limited section of

hypervariable region 1 (HVRI) of mtDNA. In the last few years wider testing has

vastly enlarged the understanding of mtDNA haplogroups. Nomenclature of

haplogroups is being constantly revised, as new SNPs are discovered. Therefore the

haplogroups assigned by the earliest of the studies in the table below are not

secure to present standards. Y-DNA being more difficult to obtain from ancient

remains, it is only comparatively recently that studies of ancient DNA have

been able to include it.

For current haplogroup trees,

with the markers that distinguish each haplogroup and sub-clade, see ISOGG's Y-DNA

Haplogroup Tree and PhyloTree's

mtDNA tree.

For maps placing some of the

following data geographically, see European

ancient mtDNA in sequential maps by

Luis Aldamiz.

|

Table 1: Mitochondrial and

Y-chromosome haplogroups extracted from historic and prehistoric human

remains in Europe and related remains in Asia and North Africa, arranged chronologically.

Note that dates for particular cultures vary from region to region, so there

is chronological overlap in the periods. |

|||||||||

|

Culture |

Country |

Site and/or Individual

pigmentation from genes |

Sex |

Date

|

Y-DNA |

mtDNA |

Source |

||

|

Palaeololithic

|

|

|

|

Haplogroup |

Additional information |

Haplogroup |

Additional information |

|

|

|

Roman Syria |

Italy/Syria |

|

c. 150 AD OR 80AD |

|

|

H2a2b1 |

16235, 16291 |

||

|

http://tade.wanclik.free.fr/adn.htm |

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_R1a1_(Y-DNA)

forum.

forum.

Introduction to genetic genealogy

DNA

studies have permitted to categorise all humans on Earth in genealogical groups

sharing one common ancestor at one given point in prehistory. They are called haplogroups. There are two kinds of

haplogroups: the paternally inherited Y-chromosome DNA(Y-DNA)

haplogroups, and the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups. They respectively

indicate the agnatic (or patrilineal) and cognatic (or matrilineal) ancestry.

Y-DNA haplogroups are useful to determine whether

two apparently unrelated individuals sharing the same surname do indeed descend

from a common ancestor in a not too distant past (3 to 20 generations). This is

achieved by comparing the haplotypes through the STR markers. Deep SNP testing allows to go back much farther

in time, and to identify the ancient ethnic group to which one's ancestors

belonged (e.g. Celtic, Germanic, Slavic, Greco-Roman, Basque, Iberian,

Phoenician, Jewish, etc.).

In Europe, mtDNA

haplogroups are quite evenly

spread over the continent, and therefore cannot be associated easily with

ancient ethnicities.

However, they can sometimes reveal some potential medical conditions (see diseases associated with mtDNA mutations).

Some mtDNA subclades are associated with Jewish ancestry, notably K1a1b1a, K1a9,d K2a2a and N1b.

DNA

Facts

· Nucleotides are the alphabet of DNA. There are

four of them : adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G) and cytosine (C). They

always go by pairs, A with T, and G with C. Such pairs are called "base

pairs". · The 46 chromosomes of human DNA are

composed of a total of 3,000 million base pairs. · The Y-chromosome possess 60 million base

pairs, against 153 million for the X chromosome. · Mitochondrial DNA is found outside the

cell's nucleus, and therefore outside of the chromosomes. It consists only of

16,569 base pairs. · A SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) is a

mutation in a single base pair. At present, only a few hundreds SNP's define

all the human haplogroups for mtDNA or Y-DNA. |

Y-DNA Haplogroups

Chronological development of Y-DNA haplogroups

- K => 40,000 years ago (probably arose in

northern Iran)

- T => 30,000 years ago (around the Red

Sea)

- J => 30,000 years ago (in the Middle

East)

- R => 28,000 years ago (in the Central

Asia)

- E1b1b => 26,000 years ago (in southern

Africa)

- I => 25,000 years ago (in the Balkans)

- R1a1

=> 21,000 years ago (in southern Russia)

- R1b => 20,000 years ago (around the

Caspian Sea or Central Asia)

- E-M78 => 18,000 years ago (in

north-eastern Africa)

- G => 17,000 years ago (between India and

the Caucasus)

- I2 => 17,000 years ago (in the Balkans)

- J2 => 15,000 years ago (in northern

Mesopotamia)

- I2b => 13,000 years ago (in Central

Europe)

- N1c1 => 12,000 years ago (in Siberia)

- I2a => 11,000 years ago (in the Balkans)

- R1b1b2 => 10,000 years ago (north or

south of the Caucasus)

- J1 => 10,000 years ago (in the Arabian

peninsula)

- E-V13 => 10,000 years ago (in the

Balkans)

- I2b1 => 9,000 years ago (in Germany)

- I2a1 => 8,000 years ago (in Sardinia)

- I2a2 => 7,500 years ago (in the Dinaric

Alps)

- E-M81 => 5,500 years ago (in the Maghreb)

- I1 => 5,000 years ago (in Scandinavia)

- R1b-L21 => 4,000 years ago (in Central or

Eastern Europe)

- R1b-S28 => 3,500 years ago (around the

Alps)

- R1b-S21 => 3,000 years ago (in Frisia or

Central Europe)

- I2b1a => less than 3,000 years ago (in

Britain)

=> More maps of the Neolithic and Bronze Age expansion

Hypothetical

map of Y-DNA haplogroup distribution in Europe about 2,000 years ago

This

map was composed by calculating modern regional densities and withdrawing the supposed influence

of migrations that took place in the last 2000 years. Only the main/dominant

haplogroups are represented for each region. Haplogroup E and R1b encompass

various subclades if the subclade not specified.

=> More on the methodology used to create the map

Large font = over 25% of the population

Small font = between 10 and 25% of the

population

European

haplogroups

The European

branch

The Indo-Europeans'

bronze weapons and horses would have given them a tremendous advantage over the

autochthonous inhabitants of Europe, namely the native haplogroup I (descendant

of Cro-Magnon), and the early Neolithic herders and farmers (G2a, J2, E-V13 and

T). This allowed R1a and R1b to replace (=> see How did R1b come to replace most of the older lineages in

Western Europe ? most

of the native male lineages, although female lineages seem to have been less

affected.

A comparison with the

Indo-Iranian invasion of South Asia shows that 40% of the male linages of

northern India are R1a, but less than 10% of the female lineages could be of

Indo-European origin. The impact of the Indo-Europeans was more severe in

Europe because European society 4,000 years ago was less developed in terms of

agriculture, technology (no bronze weapons) and population density than that of

the Indus Valley civilization. This is

particularly true of the native Western European cultures where farming arrived

much later than in the Balkans or central Europe. Greece, the Balkans and the

Carpathians were the most advanced of European societies at the time and were

the least affected in terms of haplogroup replacement. Native European Y-DNA

haplogroups (I1, I2a, I2b) also survived better in regions that were more

difficult to reach or less hospitable, like Scandinavia, Brittany, Sardinia or

the Dinaric Alps.

The first forrays of

steppe people into the Balkans happened between 4200 BCE and 3900 BCE, when

horse riders crossed the Dniester and Danube and apparently destroyed the towns

of the Gumelnita, Varna and Karanovo VI cultures in Eastern Romania and

Bulgaria. A climatic change resulting in colder winters during this exact

period probably pushed steppe herders to seek milder pastures for their stock,

while failed crops would have led to famine and internal disturbance within the

Danubian and Balkanic communities. The ensuing Cernavoda culture (4000-3200 BCE) and Ezero culture (3300-2700 BCE) seems to have had a mixed population of steppe immigrants and people from the

old tell settlements. These steppe immigrants were likely a mixture of both R1a

and R1b lineages. Many Danubian farmers would also have migrated to the

Cucuteni-Tripolye towns in the Eastern Carpathians, causing a population boom

and a north-eastward expansion until the Dnieper valley, bringing Y-haplogroups

E-V13, J2b and T in what is now central Ukraine. This precocious Indo-European

advance westward was fairly limited, due to the absence of Bronze weapons and

organised army at the time, and was indeed only possible thanks to climatic

catastrophes. The Carphatian, Danubian, and Balkanic cultures were too densely

populated and technologically advanced to allow for a massive migration.

The Bronze Age

annnounces a very different development. R1a people appear to have been the

first to successfully penetrate into the heart of Europe, with the Corded Ware (Battle Axe) culture (3200-1800 BCE) as a natural western

expansion of the Yamna culture. They went as far west as

Germany and Scandinavia. DNA analysis from the Corded Ware

culture site of Eulau confirms

the presence of R1a (but not R1b) in central Germany around 2600 BCE. The

Corded Ware migrants might well have expanded from the forest-steppe, or the

northern fringe of the Yamna culture, where R1a lineages were prevalent over

R1b ones.

R1b1b2 is thought to

have arrived in central and western Europe around 2500 BCE, by going up the

Danube from the Black Sea coast. The archeological and genetic evidence

(distribution of R1b subclades) point at several consecutive waves towards the

Danube between 2800 BCE and 2300 BCE (beginning of the Unetice culture). It is

interesting to note that this also corresponds to the end of the Maykop culture

(2500 BCE) and Kemi Oba culture (2200 BCE) on the northern shores of the Black

Sea, and their replacement by cultures descended from the northern steppes. It

can therefore be envisaged that the (mostly) R1b population from the northern

half of the Black Sea migrated westward due to pressure from other

Indo-European people (R1a) from the north, like the burgeoning

Proto-Indo-Iranian branch, linked to the contemporary Poltavka and Abashevo

cultures.

It is doubtful that the Beaker culture (2800-1900 BCE) was already

Indo-European (although they were influenced by the Corded Ware culture),

because they were the continuity of the native Megalithic cultures. It is more

likely that the beakers and horses found across western Europe during that

period were the result of trade with neighbouring Indo-European cultures,

including the first wave of R1b into central Europe. Nevertheless, it is

undeniable that the following Unetice (2300-1600

BCE), Tumulus (1600-1200

BCE),Urnfield (1300-1200

BCE) and Hallstatt (1200-750)

cultures were linked to the spread of R1b to Europe, as they abruptly introduce

new technologies and a radically different lifestyle.

Did the Indo-Europeans really invade Western Europe ?

Proponents of the

Paleolithic or Neolithic continuity model argue that bronze technology and

horses could have been imported by Western Europeans from their Eastern

European neighbours, and that no actual Indo-European invasion need be

involved. It is harder to see how Italic, Celtic and

Germanic languages were adopted by Western and Northern

Europeans without at least a small scale invasion. It has been suggested that

Indo-European (IE) languages simply spread through contact, just like

technologies, or because it was the language of a small elite and therefore

its adoption conferred a certain perceived prestige.

However people don't just change language like that because it sounds nicer

or more prestigious. Even nowadays, with textbooks, dictionaries, compulsory

language courses at school, private language schools for adults and

multilingual TV programs, the majority of the people cannot become fluent in

a completely foreign language, belonging to a different language family. The

linguistic gap between pre-IE vernaculars and IE languages was about as big

as between modern English and Chinese. English, Greek, Russian and Hindi are

all related IE languages and therefore easier to learn for IE speakers than

non-IE languages like Chinese, Arabic or Hungarian. From a linguistic point

of view, only a wide-scale migration of IE speakers could explain the

thorough adoption of IE languages in Western Europe - leaving only Basque as

a remnant of the Neolithic languages. One important archeological argument in favour of the

replacement of Neolithic cultures by Indo-European culture in the Bronze Age

comes from pottery styles. The sudden appearance of

bronze technology in Western Europe coincides with ceramics suddenly becoming

more simple and less decorated, just like in the Pontic steppes. Until then,

pottery had constantly evolved towards greater complexity and details for

over 3,000 years. People do not just decide like that to revert to a more primitive style. Perhaps one isolated tribe might

experiment with something simpler at one point, but what are the chances that

distant cultures from Iberia, Gaul, Italy and Britain all decide to undertake

such an improbable shift around the same time ? The best explanation is that

this new style was imposed by foreign invaders. In this case it is not mere

speculation; there is ample evidence that this simpler pottery is

characteristic of the steppes associated with the emergence of

Proto-Indo-European speakers. Besides pottery,

archeology provides ample evidence that the early Bronze Age in Central and

Western Europe coincides with a radical shift in food production. Agriculture

experiences an abrupt reduction in exchange for an increased emphasis on

domesticates. This is also a period when horses become more common and cow

milk is being consumed regularly. The oeverall change mimicks the steppe way

of life almost perfectly. Even after the introduction of agriculture around

5200 BCE, the Bug-Dniester culture and later steppe cultures were

characterized by an economy dominated by herding, with only limited farming.

This pattern expands into Europe exactly at the same time as bronze working. Religious beliefs

and arts undergo a complete reversal in Bronze Age

Europe. Neolithic societies in the Near East and Europe had always worshipped

female figurines as a form of fertility cult. The steppe cultures, on the

contrary, did not manufacture female figurines. As bronze technology spreads

from the Danube valley to Western Europe, symbols of fertility and fecundity

progressively disappear and are replaced by scultures of domesticated

animals. Another clue that

Indo-European steppe people came in great number to Central and Western

Europe is to be found in burial

practices. Neolithic Europeans either cremated their dead (e.g.

Cucuteni-Tripolye culture) or buried them in collective graves (this was the

case of Megalithic cultures). In the steppe, each person was buried

individually, and high-ranking graves were placed in a funeral chamber and

topped by a circular mound. The body was typically

accompanied by weapons (maces, axes, daggers), horse bones, and a dismantled

wagon (or later chariot). These characteristic burial mounds are known as kurgans in

the Pontic steppe. Men were given more sumptuous tombs than women, even among

children, and differences in hierarchy are obvious between burials. The

Indo-Europeans had a strongly hierarchical and patrilinear society, as

opposed to the more egalitarian and matrilinear cultures of Old Europe. The

proliferation of ststus-conscious male-dominant kurgans (or tumulus) in

Central Europe during the Bronze Age is a clear sign that the ruling elite

had now become Indo-European. The practice also spread to Central Asia and

Southern Siberia, two regions where R1a and R1b lineages are found nowadays,

just like in Central Europe. The ceremony of burial is one of the most

emotionally charged and personal aspect of a culture. It is highly doubtful

that people would change their ancestral practice "just to do like the

neighbours". In fact, different funerary practices have co-existed side

by side during the European Neolithic and Chalcolithic. The ascendancy of yet

another constituent of the Pontic steppe culture in the rest of Europe, and

in this case one that does not change easily through contact with neighbours,

adds up to the likelihood of a strong Indo-European migration. The adoption

of some elements of a

foreign culture tends to happen when one civilization overawes the adjacent

cultures by its superiority. This process is called 'acculturation'. However there is nothing

that indicates that the steppe culture was so culturally superior as to

motivate a whole continent, even Atlantic cultures over After linguistics and

archeology, the third category of evidence comes from genetics itself. It had first been

hypothetised that R1b was native to Western Europe, because this is where it

was most prevalent. It has since been proven that R1b haplotypes displayed

higher microsatellite diversity in Anatolia and in the Caucasus than in

Europe. European subclades are also more recent than Middle Eastern or

Central Asian ones. The main European subclade, R-P312/S116, only dates back

to approximately 3500 to 3000 BCE. It does not mean that the oldest common

ancestor of this lineage arrived in Western Europe during this period, but

that the first person who carried the mutation R-P312/S116 lived at least

5,000 years ago, assumably somewhere in the lower Danube valley or around the

Black Sea. In any case this timeframe is far too recent for a Paleolithic

origin or a Neolithic arrival of R1b. The discovery of what was thought to be

"European lineages" in Central Asia, Pakistan and India hit the

final nail on the coffin of a Paleolithic origin of R1b in Western Europe,

and confirmed the Indo-European link. All the elements

concur in favour of a large scale migration of horse-riding Indo-European

speakers to Western Europe between 2500 to 2100 BCE, contributing to the

replacement of the Neolithic or Chalcolithic lifestyle by a inherently new

Bronze Age culture, with simpler pottery, less farming, more herding, new

rituals (single graves) and new values (patrilinear society, warrior heroes)

that did not evolve from local predecessors. |

The great upheavals circa 1200 BCE

1200 BCE was a

turning point in European and Near-Eastern history. In central Europe, the

Urnfield culture evolved into theHallstatt culture, traditionally associated

with the classical Celtic civilization, which was to have a crucial influence on the development of ancient Rome. In

Italy, the Terramare culture comes to and end with the Italo-Celtic

invasions. A distinct new culture emerges in Etruria with the arrival of

settlers from the Near East, the Etruscans. In the Pontic steppes, the Srubna

culture let place to the Cimmerians, a nomadic people speaking an

Iranian or Thracian language. The Iron-age Colchian culture (1200-600 BCE) starts in the North

Caucasus region. Its further expansion to the south of the Caucasus

correspond to the first historical mentions of the Proto-Armenian branch of

Indo-European languages (circa 1200 BCE). In the central Levant the Phoenicians start establishing themselves as

significant maritime powers and building their commercial empire around the

southern Mediterranean. But the most important event of the period was

incontestably the destruction of the Near-Eastern civilizations, possibly by

theSea Peoples. The great catastrophe that ravaged the whole Eastern

Mediterranean from Greece to Egypt circa 1200 BCE is a

subject that remains controversial. The identity of the Sea Peoples has been

the object of numerous speculations. What is certain is that all the

palace-based societies in the Near-East were abruptly brought to an end by

tremendous acts of destruction, pillage and razing of cities. The most common

explanation is that the region was invaded by technologically advanced

warriors from the north, probably Indo-Europeans descended from the steppes

via the Balkans. The Hittite capital

Hattusa was destroyed in 1200 BCE, and by 1160 BCE the Empire had collapsed.

The Mycenaean cities were ravaged and abandoned through the 12th cnetury BCE,

leading to the eventual collapse of Mycenaean civilization by 1100 BCE. The

devastation of Greece followed the legendary Trojan War (1194-1187

BCE). It has been postulated that the Dorians, and Indo-European people from the

Balkans (probably coming from modern Bulgaria or Macedonia), invaded a

weakened Mycenaean Greece after the Trojan War, and finally settled in Greece

as one of the three major ethnic groups. Another hypothesis is

that the migration of the Illyrians from north-east Europe to the Balkans

displaced previous Indo-European tribes, namely the Dorians to Greece, the

Phrygians to north-western Anatolia and the Libu to Libya (after a failed

attempt to conquer the Delta region of Egypt). The Phillistines also settled

in Palestine around 1200 BCE, perhaps displaced from Anatolia. |

Haplogroup R1a (Y-DNA)

R1a is

thought to have been the dominant haplogroup among the northern and eastern

Indo-European speakers who evolved into the Indo-Iranian, Mycenaean Greek,

Macedonian, Thracian, Baltic and Slavic branches. The Proto-Indo-Europeans

originated in theYamna culture (3300-2500 BCE), in the Pontic-Caspian

steppe between modern Ukraine and south-west Russia. Their expansion is linked

to the domestication of horses in the Eurasian steppes, and the invention of

the chariot (see R1b above).

The eastern part of the

Pontic-Caspian steppes is strongly associated with the Indo-Iranian and

Balto-Slavic branches of Indo-European languages. Based on archeological,

linguistic and genetic data, it is possible to say that the pastoralist nomads

who lived in the northern Russian steppes and forest-steppes 5,000 years ago

carried predominantly R1a paternal lineages.

Nowadays, high

frequencies of R1a are found in Poland (56% of the population), Ukraine (50 to

65%), European Russia (45 to 65%), Belarus (45%), Slovakia (40%), Latvia (40%),

Lithuania (38%), the Czech Republic (34%), Hungary (32%), Croatia (29%), Norway

(28%), Austria (26%), Sweden (24%), north-east Germany (23%) and Romania (22%).

The Germanic

branch

The first expansion of R1a

took place with the westward propagation of the Corded Ware (or Battle Axe) culture (3200-1800 BCE) from the Yamna

homeland. This was the first wave of R1a into Europe, one that is responsible

for the presence of this haplogroup in Scandinavia, Germany, and a portion of

the R1a in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary or Poland. The high prevalence

of R1a in Balto-Slavic countries nowadays is not only due to the Corded Ware

expansion, but also to a long succession of later migrations from Russia, the

last of which took place from the 5th to the 1th century CE.

The Germanic branch of

Indo-European languages probably evolved from a merger of Corded-Ware R1a

(Proto-Slavic language) and the later arrival of Italo-Celtic R1b from Central

Europe. This is supported by the fact that Germanic people are hybrid R1a-R1b,

that these two haplogroups came via separate routes at different times, and

also on the linguistics of Proto-Germanic language, which shares similarities

with Italic, Celtic and Slavic languages. The Corded Ware R1a people would have

mixed with the pre-Germanic I1 aborigines to create the Nordic Bronze Age (1800-500 BCE). R1b presumably reached

Scandinavia later as a northward migration from the contemporary Hallstatt culture (1200-500 BCE). The first genuine

Germanic tongue has been estimated by linguists to have come into existence

around (or after) 500 BCE. This would confirm that it emerged as a blend of

Hallstatt Proto-Celtic and the Corded-Ware Proto-Slavic. The uniqueness of some

of the Germanic vocabulary points at borrowing from native pre-Indo-European

languages. Celtic language itself is known to have borrowed from Afro-Asiatic

languages spoken by Near-Eastern immigrants to Central Europe. The fact that

present-day Scandinavia is composed of roughly 40% of I1, 20% of R1a and 40% of

R1b reinforces the idea that Germanic ethnicity and language had acquired a

tri-hybrid character by the Iron Age.

The Baltic branch

The Baltic branch is

thought to have evolved from the Fatyanovo culture (3200-2300 BCE), the northeastern

extension of the Corded Ware culture. Early Bronze Age R1a nomads from the

northern steppes and forest-steppes would have mixed with the indigenous

Uralic-speaking inhabitants (N1c1 lineages) of the region. This is supported by

a strong presence of both R1a and N1c1 haplogroups

from southern Finland to Lithuania and the adjacent part of Russia.

The Slavic branch

The origins of the

Slavs goes back to circa 3000 BCE. The Slavic branch differentiated itself when

the Corded Ware culture (see Germanic branch above) absorbed the Cucuteni-Tripolye culture (5200-2600 BCE) of western Ukraine and

north-eastern Romania, which appears to have been composed primarily of I2a2

lineages descended directly from Paleolithic Europeans, with a

small admixture of Near-Eastern immigrants (notably E-V13 and T). Thus emerged

the hybrid Globular Amphora culture (3400-2800 BCE) in what is now

Ukraine, Belarus and Poland. It is surely during this period that I2a2, E-V13

and T spread (along with R1a) around Poland, Belarus and western Russia, explaining

why eastern and northern Slavs (and Lithuanians) have a considerable incidence

of haplogroups I2a2 with a bit of E and T. After just a few centuries, this

hybridised culture faded away into the dominant Corded Ware culture.

The Corded Ware period

was followed by the Trzciniec (1700-1200

BCE), Lusatian (1300-500

BCE), Chernoles (1025-700

BCE) andMilograd (600

BCE-100 CE) cultures in north-east Slavic countries. The last important Slavic migration

is thought to have happened in the 6th century CE, from Ukraine to Poland, the

Czech Republic and Slovakia, filling the vacuum left by eastern Germanic tribes

who invaded the Roman Empire.

Historically, no other

part of Europe was invaded a higher number of times by

steppe peoples than the Balkans. Chronologically, the first R1a invaders came

with the westward expansion of the Corded Ware culture (from about 3200 BCE),

then the Mycenaean invasion (1600 BCE), followed by the Thracians (1500 BCE), the

Illyrians (around 1200 BCE), the Huns and the Alans (400 CE), the Avars, the

Bulgars and the Serbs (all around 600 CE), and the Magyars (900 CE), among

others. These peoples originated from different parts of the Eurasian steppes,

anywhere between Eastern Europe and Central Asia, which is why such high STR

diversity is found within Balkanic R1a nowadays. It is not yet possible to

determine the ethnic origin for each variety of R1a, apart from the fact that

about any R1a is associated with tribes from Eurasian steppe at one point in

history.

The Indo-Iranian

branch

Proto-Indo-Iranian

speakers, the people who later called themselves 'Aryans' in the Rig Veda and

the Avesta, originated in the Sintashta-Petrovka

culture (2100-1750 BCE), in the Tobol and Ishim valleys, east of the Ural

Mountains. It was founded by pastoralist nomads from the Abashevo culture (2500-1900 BCE), ranging from the

upper Don-Volga to the Ural Mountains, and thePoltavka culture (2700-2100 BCE), extending from the lower

Don-Volga to the Caspian depression. The Sintashta-Petrovka culture was the

first Bronze Age advance of the Indo-Europeans west of the Urals, opening the

way to the vast plains and deserts of Central Asia to the metal-rich Altai

mountains. The Aryans quickly expanded over all Central Asia, from the shores

of the Caspian to southern Siberia and the Tian Shan, through trading, seasonal

herd migrations, and looting raids.

Horse-drawn war

chariots seem to have been invented by Sintashta people around 2100 BCE, and

quickly spread to the mining region of Bactria-Margiana (modern border of

Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan). Copper had been

extracted intensively in the Urals, and the Proto-Indo-Iranians from

Sintashta-Petrovka were exporting it in huge quantities to the Middle East.

They appear to have been attracted by the natural resources of the Zeravshan valley for a Petrovka copper-mining colony

was established in Tugai around 1900 BCE, and tin was extracted soon afterwards

at Karnab and Mushiston. Tin was an especially valued resource in the late

Bronze Age, when weapons were made of copper-tin alloy, stronger than the more

primitive arsenical bronze. In the 1700's BCE, the Indo-Iranians expanded to

the lower Amu Darya valley

and settled in irrigation farming communities (Tazabagyab culture). By 1600

BCE, the old fortified towns of Margiana-Bactria were abandoned, submerged by

the northern steppe migrants. The group of Central Asian cultures under

Indo-Iranian influence is known as the Andronovo horizon, and lasted until 800 BCE.

The Indo-Iranian migrations progressed further south across the

Hindu Kush. By 1700 BCE, horse-riding pastoralists had penetrated into

Balochistan (south-west Pakistan). The Indus valley succumbed circa 1500 BCE,

and the northern and central parts of the Indian subcontinent were taken over

by 500 BCE. Westward migrations led Old Indic Sanskrit speakers riding war

chariots to Assyria, where they became the Mitanni rulers

from circa 1500 BCE. The Medes, Parthians and Persians, all Iranian speakers from the

Andronovo culture, moved into the Iranian plateau from 800 BCE. Those that

stayed in Central Asia are remembered by history as the Scythians, while the Yamna descendants who

remained in the Pontic-Caspian steppe became known as the Sarmatians to

the ancient Greeks and Romans.

The Indo-Iranian

migrations have resulted in high R1a frequencies in southern Central Asia, Iran

and the Indian subcontinent. The highest frequency of R1a (about 65%) is

reached in a cluster around Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and northern Afghanistan. In

India and Pakistan, R1a ranges from 15 to 50% of the population, depending on

the region, ethnic group and caste. R1a is generally stronger is the North-West

of the subcontinent, and weakest in the Dravidian-speaking South (Tamil Nadu,

Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh) and from Bengal eastward. Over 70% of the

Brahmins (highest caste in Hindusim) belong to R1a1, due to a founder effect.

Maternal lineages in

South Asia are, however, overwhelmingly pre-Indo-European. For instance, India

has over 75% of "native" mtDNA M and R lineages and 10% of East Asian

lineages. In the residual 15% of haplogroups, approximately half are of Middle

Eastern origin. Only about 7 or 8% could be of "Russian"

(Pontic-Caspian steppe) origin, mostly in the form of haplogroup U2 andW (although

the origin of U2 is still debated). European mtDNA lineages are much more

common in Central Asia though, and even in Afghanistan and northern Pakistan.

This suggests that the Indo-European invasion of India was conducted mostly by

men through war, and the first major settlement of women was in northern

Pakistan, western India (Punjab to Gujarat) and northern India (Uttar Pradesh),

where haplogroups U2 and W are the most common.

The Greek branch

Little is known about

the arrival of Proto-Greek speakers from the steppes. The Mycenaean culture

commenced circa 1650 BCE and is clearly an imported steppe culture. The close

relationship between Mycenaean and Proto-Indo-Iranian languages suggest that

they split fairly late, some time between 2500 and 2000 BCE. Archeologically,

Mycenaean chariots, spearheads, daggers and other bronze objects show striking

similarities with the Seima-Turbino culture (c. 1900-1600 BCE) of the northern

Russian forest-steppes, known for the great mobility of its nomadic warriors

(Seima-Turbino sites were found as far away as Mongolia). It is therefore

likely that the Mycenaean descended from Russia to Greece between 1900 and 1650

BCE, where they intermingled with the locals to create a new unique Greek

culture.

Distribution of

haplogroup R1a in Eurasia

|

Table 2: Y-chromosome STR

haplotypes. Haplotype labels in column 2 have no official status. They are simply

for reference between tables on this page. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Haplogroup |

Haplotype |

DYS 19 |

385a |

385b |

388 |

389-1 |

389-2 |

390 |

391 |

392 |

393 |

426 |

437 |

438 |

439 |

444 |

446 |

447 |

448 |

449 |

456 |

458 |

459 |

481 |

635 |

YGATA |

H4 |

|

R1a |

Ri |

15 |

11 |

13? |

|

13 |

30 |

23 |

11 |

11 |

13 |

|

14 |

11 |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16 |

11 |

14 |

12 |

13 |

16* |

25 |

10 |

11 |

13 |

12 |

|

|

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R1a1 |

Rii |

16 |

11 |

14 |

|

14 |

32 |

25 |

11 |

11 |

13 |

|

14 |

11 |

10 |

|

|

|

20 |

|

16 |

15 |

|

|

23 |

12 |

|

|

R1a1 |

Riii |

17 |

11 |

14 |

|

13 |

31 |

24 |

11 |

11 |

13 |

|

14 |

11 |

10 |

|

|

|

20 |

|

16 |

15 |

|

|

23 |

13 |

|

|

R1a1 |

Riv |

|

11 |

14 |

|

13 |

31 |

24 |

11 |

11 |

13 |

|

14 |

11 |

10 |

|

|

|

20 |

|

16 |

15 |

|

|

23 |

|

|

|

R1a1 |

Rv |

16 |

11 |

14 |

|

13 |

31 |

24 |

11 |

11 |

13 |

|

14 |

11 |

10 |

|

|

|

20 |

|

16 |

15 |

|

|

23 |

13 |

|

|

R1a1 |

Rvi |

16 |

11 |

14 |

|

14 |

31 |

25 |

11 |

11 |

13 |

|

14 |

11 |

10 |

|

|

|

20 |

|

16 |

15 |

|

|

23 |

12 |

|

|

R1a1 |

Rvii |

|

11 |

14 |

|

14 |

31 |

25 |

11 |

11 |

13 |

|

14 |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

16 |

15 |

|

|

23 |

12 |

|

|

R1a1 |

Rviii |

17 |

11 |

14 |

|

13 |

31 |

24 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

|

14 |

11 |

10 |

|

|

|

20 |

|

16 |

15 |

|

|

23 |

13 |

|

Luke the Evangelist

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Saint Luke" redirects here. For other

uses, see Saint Luke

(disambiguation).

|

Saint Luke |

|

|

St Luke displaying a painting of Mary by Guercino |

|

|

Apostle, Evangelist, Martyr |

|

|

Born |

|

|

Died |

c. 84, near Boeotia, Greece |

|

Venerated in |

Roman Catholic

Church, Orthodox Church, Eastern

Catholic Churches,Anglican Church, Lutheran Church, some other Protestant Churches |

|

Majorshrine |

Padua, Italy |

|

18 October |

|

|

Artists, Physicians, Surgeons, and others[1] |

|

Luke the Evangelist (Ancient Greek: Λουκᾶς Loukas) was an Early Christian writer who theChurch Fathers such as Jerome and Eusebius said

was the author of the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles.

The Roman Catholic Church venerates him as Saint Luke, patron saint of physicians,surgeons, students, butchers, and artists; his feast day is 18

October.

Contents

[hide] ·

1 Life ·

5 The Relics of St. Luke the Evangelist ·

8 Notes |

[edit]Life

Saint Luke was a physician and lived in Greece in the city of Antioch.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

His earliest notice is in Paul's Epistle to Philemon,

verse 24. He is also mentioned inColossians 4:14

and 2 Timothy 4:11,

two works commonly ascribed to Paul. The next earliest account of Luke is in

the Anti-Marcionite Prologue

to the Gospel of Luke, a document once thought to date to the 2nd century,

but which has more recently been dated to the later 4th century. Helmut Koester, however, claims that the

following part – the only part preserved in the original Greek –

may have been composed in the late 2nd century:

|

“ |

Luke, a native of Antioch, by profession a physician.[8] He

had become a disciple of the apostle Paul and later followed Paul until his

[Paul's] martyrdom. Having served the Lord continuously, unmarried and without

children, filled with the Holy Spirit he died at the age of 84 years.

(p. 335) |

” |

Epiphanius states that Luke was one of the Seventy (Panarion 51.11), and John Chrysostom indicates at one point that the

"brother" Paul mentions in 2 Corinthians 8:18 is either Luke or Barnabas. J. Wenham asserts that Luke was

"one of the Seventy, the Emmaus disciple,

Lucius of Cyrene and Paul's kinsman." Not all scholars are as confident of

all of these attributes as Wenham is, not least because Luke's own statement at

the beginning of the Gospel of Luke (1:1–4) freely admits that he was not an eyewitness

to the events of the Gospel.

If accepted that Luke was in fact the author of the Gospel bearing

his name and also the Acts of

the Apostles, certain details of his personal life can be reasonably

assumed. While he does exclude himself from those who were eyewitnesses to

Jesus' ministry, he repeatedly uses the word "we" in describing the

Pauline missions in Acts of

the Apostles, indicating that he was personally there at those times.[9]

There is similar evidence that Luke resided in Troas,

the province which included the ruins of ancient Troy, in that he writes in Acts in the third person about Paul and his

travels until they get to Troas, where he switches to the first person plural.

The "we" section of Acts continues until the group leaves Philippi, when his writing goes back to the

third person. This change happens again when the group returns to Philippi.

There are three "we sections" in Acts,

all following this rule. Luke never stated, however, that he lived in Troas,

and this is the only evidence that he did.

The composition of the writings, as well as the range of

vocabulary used, indicate that the author was an educated man. The quote in the

Letter of Paul to the Colossians differentiating between Luke and other

colleagues "of the circumcision"[10] has

caused many to speculate that this indicates Luke was a Gentile. If this were true, it would make Luke

the only writer of the New Testament who can clearly be identified as not being

Jewish. However, that is not the only possibility. The phrase could just as

easily be used to differentiate between thoseChristians who strictly observed the rituals of Judaism and those who did not.[9]

Luke died at age

[edit]Luke

as a Historian

See also: Historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles, Census of Quirinius, and Chronology of Jesus

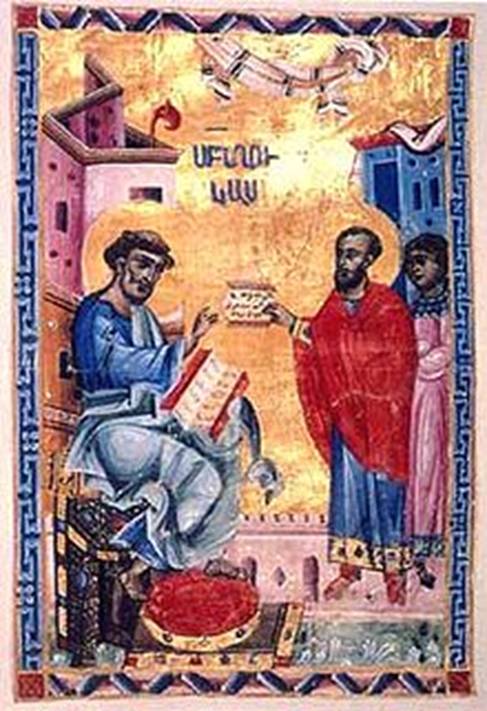

A medieval Armenian

illumination, byToros Roslin.

Most scholars understand Luke's works (Luke-Acts) in the tradition

of Greek historiography.[12] The

preface of The Gospel of Luke (1:1-4) drawing on historical

investigation is believed to have identified the work to the readers as

belonging to the genre of history.[13] There

is some disagreement about how best to treat Luke's writings, with some

historians regarding Luke as highly accurate, and others taking a more critical

approach.

Archaeologist Sir William Ramsay wrote that "Luke is a historian

of the first rank; not merely are his statements of fact trustworthy...[he]

should be placed along with the very greatest of historians."[14] Professor

of classics at Auckland University, E.M. Blaiklock, wrote: "For accuracy of detail,

and for evocation of atmosphere, Luke stands, in fact, with Thucydides. The Acts of the Apostles is not

shoddy product of pious imagining, but a trustworthy record...it was the

spadework of archaeology which first revealed the truth."[15] New

Testament scholar Colin

Hemer has made a

number of advancements in understanding the historical nature and accuracy of

Luke's writings.[16]

On the purpose of Acts, New Testament Scholar Luke Timothy Johnson has noted that "Luke's account is

selected and shaped to suit his apologetic interests, not in defiance of but in

conformity to ancient standards of historiography."[17] Such

a position is shared by most commentators such as Richard Heard who sees

historical deficiencies as arising from "special objects in writing and to

the limitations of his sources of information." [18] Robert M. Grant has noted that although Luke saw

himself within the historical tradition, his work contains a number of

statistical improbabilities such as the sizable crowd addressed by Peter in

Acts 4:4. He has also noted chronological difficulties whereby Luke "has

Gamaliel refer to Theudas and Judas in the wrong order, and Theudas actually

rebelled about a decade after Gamaliel spoke(5:36-7)'[12]

The Catholic Encyclopedia talks of Luke's 'extreme accuracy'[19], while noting that hypotheses to

reconcile a claim allegedly made by Luke that Annas and Caiaphas were

High Priest simultaneously, while 'more or less plausible', are 'not strictly

accurate'[20], and the List of High

Priests of Israel shows

the two to be separated by two years and three incumbents.

It has also been noted that accuracy in some details does not

necessarily imply accuracy in others, and vice versa.

[edit]Iconography

Luke the Evangelist

painting the first iconof

the Virgin Mary.

Another Christian tradition states that he was the first iconographer, and painted pictures of theVirgin Mary (for example, The

Black Madonna of Częstochowa or Our Lady of Vladimir)

and ofPeter and

Paul. Thus late medieval guilds of St Luke in the cities of Flanders, or the Accademia di San Luca ("Academy of St Luke") in

Rome, imitated in many other European cities during the 16th century, gathered

together and protected painters. The tradition that Luke painted icons of Mary

and Jesus has been common, particularly in Eastern Orthodoxy. The tradition also

has support from the Saint Thomas

Christians of India

who claim to still have one of the Theotokos icons

that St Luke painted and Thomas brought to India.[21]

[edit]New

Testament books

See also Gospel of Luke: Author and Acts of the Apostles:

Authorship

Some scholars attribute

to Luke the third Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles,

which is clearly meant to be read as a sequel to the Gospel account. Other scholars

question Luke's authorship of these books. Many secular scholars give credit to

Luke's abilities as an historian. Both books are dedicated to one Theophilus and no scholar seriously doubts that

the same person wrote both works, though neither work contains the name of its

author.

Many argue that the author of the book must have been a companion

of the Apostle Paul, because of several passages in Acts

written in the first person plural (known as the We Sections). These verses (see

Acts 16:10–17, 20:5–15, 21:1–18, etc.) seem to indicate the author was

traveling with Paul during parts of his journeys. Some scholars report that, of

the colleagues that Paul mentions in his epistles, the process of elimination

leaves Luke as the only person who fits everything known about the author of

Luke/Acts.

Additionally, the earliest manuscript of the Gospel (Papyrus Bodmer XIV/XV = P75), dated

circa AD 200, ascribes the work to Luke; as didIrenaeus, writing circa AD 180; and the Muratorian fragment from AD 170.[22] Scholars

defending Luke's authorship say there is no reason for early Christians to

attribute these works to such a minor figure if he did not in fact write them,

nor is there any tradition attributing this work to any other author.

Luke and

the Madonna, Altar of the Guild of St. Luke, Hermen

Rode, Lübeck 1484.

[edit]The Relics of St. Luke

the Evangelist

The remains of St. Luke were brought to Padua, Italy, sometime

before 1177, according to tradition.[23][24] In

1992, the then Greek Orthodox Metropolitan Ieronymos of Thebes and Levathia

(currently the Archbishop of Greece) requested from Bishop Antonio Mattiazzo of

Padua the return of a "a significant fragment of the relics of St. Luke to

be placed on the site where the holy tomb of the Evangelist is located and

venerated today". This prompted a scientific investigation of the relics

in Padua, and by numerous lines of empirical evidence (archeological analyses

of the Tomb in Thebes and the Reliquary of Padua, anatomical analyses of the

remains, Carbon-14 dating, comparison with the purported skull of the

Evangelist located in Prague) confirmed that these were the remains of an

individual of Syrian descent who died between 130 and

[edit]See

also

[edit]References

§

I. Howard Marshall. Luke:

Historian and Theologian. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press.

§

F.F. Bruce, The

Speeches in the Acts of the Apostles. London:

The Tyndale Press, 1942.[1]

§

Helmut Koester. Ancient

Christian Gospels. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Trinity Press International,

1999.

§

Burton L. Mack. Who

Wrote the New Testament?: The Making of the Christian Myth. San Francisco,

California: HarperCollins, 1996.

§

J. Wenham, "The Identification of Luke", Evangelical Quarterly 63 (1991), 3–44

[edit]Notes

1. ^ "Saint Luke the Evangelist". Star Quest Production Network. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

2.

^ The New Testament

Documents: Their Origin and Early History, George Milligan, 1913, Macmillan and Co.

limited, p. 149

3.

^ Saint Luke Catholic Online article

4.

^ Saints: A Visual Guide, Edward Mornin, Lorna

Mornin, 2006, Eerdmans Books, p. 74

5.

^ Saint

Luke Catholic Encyclopedia article

6.

^ New Outlook, Alfred Emanuel Smith,

1935, Outlook Pub. Co., p. 792

7.

^ New Testament Studies. I.

Luke the Physician: The Author of the Third Gospel, Adolf von Harnack,

1907, Williams & Norgate; G.P. Putnam's Sons, p. 5

8.

^ A Commentary on the

Original Text of the Acts of the Apostles, Horatio Balch Hackett, 1858, Gould and

Lincoln; Sheldon, Blakeman & Co., p. 12

9.

^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica,

Micropædia vol. 7, p. 554–555. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc,

1998. ISBN 0-85229-633-0.

10.

^ Colossians 4:10 and 11,

compared with 14

11.

^ Michael Walsh, ed.

"Butler's Lives of the Saints." (HarperCollins Publishers: New York,

1991), pp. 342.

12.

^ a b Grant, Robert M., "A Historical

Introduction to the New Testament" (Harper and Row, 1963) http://www.religion-online.org/showchapter.asp?title=1116&C=1230

13.

^ Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses.

117.

14.

^ Ramsay, BRDTNT, 222

15.

^ Blaiklock, The

Archaeology of the New Testament, page 96, Zondervan Publishing Houst, Grand

Rapids, Michigan, 1970.

16.

^ Hemer, "The Book of

Acts in the Setting of Hellenic History", 104–107, as summarized by

MacDowell.

17.

^ Johnson, Luke Timothy

"The Acts of the Apostles" (The Liturgical Press, 1992), pp. 474-476,

cited at http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/luke.html

18.

^ Heard, Richard: An

Introduction to the New Testament Chapter 13: The Acts of the Apostles, Harper

& Brothers, 1950 http://www.religion-online.org/showbook.asp?title=531

19.

^ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09420a.htm#VI

20.

^ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01536a.htm

21.

^ Father H. Hosten in his book Antiquities notes the following "The picture

at the mount is one of the oldest, and, therefore, one of the most venerable Christian

paintings to be had in India. Other traditions hold that St. Luke painted two

icons which currently reside in Greece: the Theotokos Mega Spileotissa (Our

Lady of the Great Cave, where supposedly St. Luke lived for a period of time in

asceticism) and Panagia Soumela, and Panagia Kykkou which resides in

Cyprus."

22.

^ Brown, Raymond E. An Introduction to the New

Testament, p. 267. Anchor Bible; 1st edition (October 13, 1997). ISBN 978-0385247672.

23.

^ a b The Beloved Physician St. Luke, Padua.

24.

^ a b Wade, Nicholas. "Body of St. Luke' Gains Credibility." New York Times, October 16, 2001.

[edit]External

links

|

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Luke

the Evangelist |

§

Gospel of Saint Luke ( English And Arabic)

§

Acts of Saint Luke ( English And Arabic)

§

About

Saint Luke( English And Arabic)

§

Saint

Luke Coptic Orthodox Church in Egypt

§

Saint

Luke Orthodox christian Radio in English and Arabic

§

Biblical Interpretation of Texts of Saint Luke

§

Early Christian Writings: Gospel

of Luke e-texts, introductions

§

Gospel of Saint Luke Audio in Arabic

§

National Academy of Sciences on Luke the Evangelist

§

Photo of the grave of Luke in Padua (in German)

§

DNA testing of the Saint Luke corpse

|

Categories: Seventy

Disciples | 80s deaths | Greek saints | Greek

Roman Catholic saints | Christian

martyrs of the Roman era | New Testament

people | Saints

from the Holy Land | Palestinian

Roman Catholic saints | Syrian saints | Syrian

Roman Catholic saints |Anatolian

Roman Catholic saints | Saints from

Anatolia | Black

Madonna of Częstochowa | Ancient

Greek physicians | Ancient

Syrian physicians | Christianity

in Roman Achaea | Ancient Boeotia | 1st-century

Christian martyr saints

|

ST LUKE THE EVANGELIST |

|

Feast: October 18 |

|

The great apostle of the Gentiles, or rather the Holy Ghost by his pen, is the panegyrist of this glorious evangelist, and his own inspired writings are the highest standing and most authentic commendation of his sanctity, and of those eminent graces which are a just subject of our admiration, but which human praises can only extenuate. St. Luke was a native of Antioch, the metropolis of Syria, a city famous for the agreeableness of its situation, the riches of its traffic, its extent, the number of its inhabitants, the politeness of their manners, and their learning and wisdom. Its schools were the most renowned in all Asia, and produced the ablest masters in all arts and sciences. St. Luke acquired a stock of learning in his younger years, which we are told he improved by his travels in some parts of Greece and Egypt. St. Jerome assures us he was very eminent in his profession, and St. Paul, by calling him his most dear physician,[1] seems to indicate that he had not laid it aside. Besides his abilities in physic, he is said to have been very skillful in painting. The Menology of the Emperor Basil, compiled in 980, Nicephorus,[2] Metaphrastes, and other modern Greeks quoted by Gretzer in his dissertation on this subject, speak much of his excelling in this art, and of his leaving many pictures of Christ and the Blessed Virgin. Though neither the antiquity nor the credit of these authors is of great weight, it must be acknowledged, with a very judicious critic, that some curious anecdotes are found in their writings. In this particular, what they tell us is supported by the authority of Theodorus Lector, who lived in 518, and relates[3] that a picture of the Blessed Virgin painted by St. Luke was sent from Jerusalem to the Empress Pulcheria, who placed it in the church of Hodegorum which she built in her honour at Constantinople. Moreover, a very ancient inscription was found in a vault near the Church of St. Mary in via lata in Rome, in which it is said of a picture of the Blessed Virgin Mary discovered there, "One of the seven painted by St. Luke." Three or four such pictures are still in being; the principal is that placed by Paul V in the Barghesian chapel in St. Mary Major. St. Luke was a proselyte to the Christian religion, but whether from Paganism or rather from Judaism is uncertain; for many Jews were settled in Antioch, but chiefly such as were called Hellenists, who read the Bible in the Greek translation of the Septuagint. St. Jerome observes from his writings that he was more skilled in Greek than in Hebrew, and that therefore he not only always makes use of the Septuagint translation, as the other authors of the New Testament who wrote in Greek do, but he refrains sometimes from translating words when the propriety of the Greek tongue would not bear it. Some think he was converted to the faith by St. Paul at Antioch; others judge this improbable, because that apostle nowhere calls him his son, as he frequently does his converts. St. Epiphanius makes him to have been a disciple of our Lord; which might be for some short time before the death of Christ, though this evangelist says he wrote his gospel from the relations of those "who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word."[4] Nevertheless, from these words many conclude that he became a Christian at Antioch only after Christ's ascension. Tertullian positively affirms that he never was a disciple of Christ whilst he lived on earth.[5] No sooner was he enlightened by the Holy Ghost and initiated in the school of Christ but he set himself heartily to learn the spirit of his faith and to practice its lessons. For this purpose he studied perfectly to die to himself, and, as the church says of him, "He always carried about in his body the mortification of the cross for the honour of the divine name." He was already a great proficient in the habits of a perfect mastery of himself, and of all virtues, when he became St. Paul's companion in his travels and fellow-labourer in the ministry of the gospel. The first time that in his history of the missions of St. Paul[6] he speaks in his own name in the first person is when that apostle sailed from Troas into Macedon in the year 51, soon after St. Barnabas had left him, and St. Irenaeus begins from that time the voyages which St. Luke made with St. Paul.[7] Before this he had doubtless been for some time an assiduous disciple of that great apostle; but from the time he seems never to have left him unless by his order upon commissions for the service of the churches he had planted. It was the height of his ambition to share with that great apostle all his toils, fatigues, dangers, and sufferings. In his company he made some stay at Philippi in Macedon; then he travelled with him through all the cities of Greece, where the harvest every day grew upon their hands. St. Paul mentions him more than once as the companion of his travels, he calls him "Luke the beloved physician,"[8] his "fellow labourer."[9] Interpreters usually take Lucius, whom St. Paul calls his kinsman[10], to be St. Luke, as the same apostle sometimes gives a Latin termination to Silas, calling him Sylvanus. Many with Origen, Eusebius, and St. Jerome say that when St. Paul speaks of his own gospel[11] he means that of St. Luke, though the passage may be understood simply of the gospel which St. Paul preached. He wrote this epistle in the year 57, four years before his first arrival at Rome. St. Luke mainly insists in his gospel upon what relates to Christ's priestly office; for which reason the ancients, in accommodating the four symbolical representations, mentioned in Ezekiel, to the four evangelists, assigned the ox or calf as an emblem of sacrifices to St. Luke. It is only in the Gospel of St. Luke that we have a full account of several particulate relating to the Annunciation of the mystery of the Incarnation to the Blessed Virgin, her visit to St. Elizabeth, the parable of the prodigal son, and many other most remarkable points. The whole is written with great variety, elegance, and perspicuity. An incomparable sublimity of thought and diction is accompanied with that genuine simplicity which is the characteristic of the sacred penman; and by which the divine actions and doctrine of our Blessed Redeemer are set off in a manner which in every word conveys his holy spirit, and unfolds in every tittle the hidden mysteries and inexhausted riches of the divine love and of all virtues to those who, with a humble and teachable disposition of mind, make these sacred oracles the subject of their assiduous devout meditation. The dignity with which the most sublime mysteries, which transcend all the power of words and even the conception and comprehension of all created beings, ate set off without any pomp of expression has in it something divine; and the energy with which the patience, meekness, charity, and beneficence of a God made man for us are described, his divine lessons laid down, and the narrative of his life given, but especially the dispassionate manner in which his adorable sufferings and death are related, without the least exclamation or bestowing the least harsh epithet on his enemies, is a grander and more noble eloquence on such a theme, and a more affecting and tender manner of writing' than the highest strains or the finest ornaments of speech could be. This simplicity makes the great actions speak themselves, which all borrowed eloquence must extenuate. The sacred penmen in these writings were only the instruments or organs of the Holy Ghost; but their style alone suffices to evince how perfectly free their souls were from the reign or influence of human passions, and in how perfect a degree they were replenished with all those divine virtues and that heavenly spirit which their words breathe. About the year St. Luke did not forsake his master after he was released from his confinement. That apostle in his last imprisonment at Rome writes that the rest had all left him, and that St. Luke alone was with him.[13] St. Epiphanius says[14] that after the martyrdom of St. Paul, St. Luke preached in Italy, Gaul, Dalmatia, and Macedon. By Gaul some understand Cisalpine Gaul, others Galatia. Fortunatus and Metaphrastus say he passed into Egypt and preached in Thebais. Nicephorus says he died at Thebes in Boeotia, and that his tomb was shown near that place in his time; but seems to confound the evangelist with St. Luke Stiriote, a hermit of that country. St. Hippolytus says[15] St. Luke was crucified at Elaea in Peloponnesus near Achaia. The modern Greeks tell us he was crucified on an olive tree. The ancient African Martyrology of the fifth age[16] gives him the titles of Evangelist and Martyr. St. Gregory Nazianzen,[17] St. Paulinus,[18] and St. Gaudentius of Brescia[19] assure us that he went to God by martyrdom. Bede, Ado, Usuard, and Baronius in the Martyrologies only say he suffered much for the faith, and died very old in Bithynia. That he crossed the straits to preach in Bithynia is most probable, but then he returned and finished his course in Achaia; under which name Peloponnesus was then comprised. The modern Greeks say he lived fourscore and four years; which assertion has crept into St. Jerome's account of St. Luke,[20] but is expunged by Martianay, who found those words wanting in all old manuscripts. The bones of St. Luke were translated from Patras in Achaia in 357 by order of the Emperor Constantius, and deposited in the Church of the Apostles at Constantinople,[21] together with those of St. Andrew and St. Timothy. On the occasion of this translation some distribution was made of the relics of St. Luke; St. Gaudentius procured a part for his church at Brescia.[22] St. Paulinus possessed a portion in St. Felix's Church at Nola, and with a part enriched a church which he built at Fondi.[23] The magnificent Church of the Apostles at Constantinople was built by Constantine the Great,[24] whose body was deposited in the porch in a chest of gold, the twelve apostles standing round his tomb.[25] When this church was repaired by an order of Justinian, the masons found three wooden chests or coffins in which, as the inscriptions proved, the bodies of St. Luke, St. Andrew, and St. Timothy were interred.[26] Baronius mentions that the head of St. Luke was brought by St. Gregory from Constantinople to Rome, and laid in the church of his monastery of St. Andrew.[27] Some of his relics are kept in the great Grecian monastery on Mount Athos in Greece.[28] Christ, our divine Legislator, came not only to be our model by his example, and our Redeemer by the sacrifice of his adorable blood, but also and our Redeemer by the sacrifice of his adorable blood, but also to be our doctor and teacher by his heavenly doctrine. With what earnestness and diligence, with what awful respect, ought we to listen to and assiduously meditate upon his divine lessons, which we read in his gospels or hear from the mouths of his ministers who announce to us his word and in his name, or by his authority and commission. It is by repeated meditation that the divine word sinks deep into our hearts. What fatigues and sufferings did it cost the Son of God to announce it to us? How many prophets, how many apostles, evangelists, and holy ministers has he sent to preach the same for the sake of our souls? How intolerable is our contempt of it? our sloth and carelessness in receiving it? |

Saint Luke

Feastday: October 18

Patron Physicians and Surgeons

Saint Luke

Luke, the writer of

the Gospel and theActs of the Apostles, has been identified

with St. Paul's "Luke, the beloved physician" (Colossians 4:14). We

know few other facts about Luke's life from Scripture and from early Church historians.

It is believed that Luke was born a

Greek and a Gentile. InColossians 10-14 speaks of those friends who are

with him. He first mentions all those "of the circumcision" -- in

other words,Jews -- and he does not include Luke in this group. Luke's gospel shows

special sensitivity to evangelizing Gentiles. It is only in his gospel that we

hear the parable of the Good Samaritan, that we hear Jesus praising the faith of Gentiles such as the widow of Zarephath and Naaman the Syrian

(Lk.4:25-27), and that we hear the story of the one grateful leper who is a

Samaritan (Lk.17:11-19). According to the early Church historian Eusebius Luke was born at Antioch in Syria.

In our day, it

would be easy to assume that someone who was a doctor was rich, but scholars have argued

that Luke might have been born a slave. It was

not uncommon for families to educate slaves in medicine so that they would have a resident family physician. Not only do we have Paul's

word, but Eusebius, Saint Jerome, Saint Irenaeus and Caius, a second-century

writer, all refer to Luke as a physician.

We have to go to Acts to follow the trail of Luke's Christian ministry. We know nothing about his conversion but looking at the language of Acts we can see where he joined Saint Paul.

The story of the Acts is written in the third person, as an

historian recording facts, up until the sixteenth chapter. In Acts 16:8-9 we hear of Paul's company

"So, passing by Mysia, they went down to Troas. During the night Paul had

a vision: there stood a man of Macedonia pleading with him and

saying, 'Come over to Macedonia and help us.' " Then suddenly in 16:10

"they" becomes "we": "When he had seen the vision, we

immediately tried to cross over to Macedonia, being convinced that God had called us to proclaim thegood news to them."

So Luke first joined Paul's company at Troas at about the year 51 and accompanied

him into Macedonia where they traveled first to Samothrace, Neapolis, and

finally Philippi.Luke then switches back to the third person which seems to indicate he was not thrown

into prison with Paul and that when Paul left Philippi Luke stayed behind to encourage the Church

there. Seven years passed before Paul returned to the area on his third

missionary journey. In Acts 20:5, the switch to "we"

tells us that Luke has left Philippi to rejoin Paul in Troas in 58 where they first met up. They

traveled together through Miletus, Tyre, Caesarea, to Jerusalem.

Luke is the loyal

comrade who stays with Paul when he is imprisoned in Rome about the year 61: "Epaphras, my

fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus, sends greetings to you, and so

do Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke, my fellow workers" (Philemon 24).

And after everyone else deserts Paul in his final imprisonment and sufferings,

it is Luke who remains with Paul to the end:

"Only Luke is with me" (2 Timothy 4:11).

Luke's inspiration and information for his Gospel and Acts came from his close association with

Paul and his companions as he explains in his introduction to the Gospel:

"Since many have undertaken to set down an orderly account of the events

that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed on to us by those

who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word, I too

decided, after investigating everything carefully from the very first, to write

an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus" (Luke 1:1-3).

Luke's unique

perspective on Jesus can be seen in the six miracles and

eighteen parablesnot

found in the other gospels. Luke's is the gospel of the poor and of social

justice. He is the one who tells the story of Lazarus and the Rich Man who ignored him. Luke is the one who uses "Blessed are

the poor" instead of "Blessed are the poor in spirit" in the

beatitudes. Only in Luke's gospel do we hear Mary 's Magnificat where she proclaims that God "has brought down the powerful

from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away

empty" (Luke 1:52-53).

Luke also has a

special connection with the women in Jesus' life, especially Mary. It is only

in Luke's gospel that we hear the story of the Annunciation, Mary's visit to Elizabethincluding

the Magnificat, the Presentation, and the story of Jesus' disappearance in

Jerusalem. It is Luke that we have to thank for the

Scriptural parts of the Hail Mary: "Hail Mary full of grace" spoken at the

Annunciation and "Blessed are you and blessed is the fruit of your womb

Jesus" spoken by her cousin Elizabeth.

Forgiveness and

God's mercy to sinners is also of first importance to Luke. Only in Lukedo we hear the story

of the Prodigal Son welcomed back by the overjoyed father. Only inLuke do we hear the story of the forgiven woman disrupting the feast by washing Jesus'

feet with her tears. Throughout Luke's gospel, Jesus takes the side of the sinner who wants

to return to God's mercy.

Reading Luke's

gospel gives a good idea of his character as one who loved the poor, who wanted

the door to God's kingdom opened to all, who respected women, and who sawhope in God's mercy for everyone.

The reports of

Luke's life after Paul's death are conflicting.

Some early writers claim he was martyred, others say he lived a long life. Some

say he preached in Greece, others in Gaul. The earliest tradition we have says

that he died at 84 Boeotia after settling in Greeceto

write his Gospel.

A tradition that Luke was a painter

seems to have no basis in fact. Several images of Maryappeared in later

centuries claiming him as a painter but these claims were proved false. Because

of this tradition, however, he is considered a patron of painters of pictures

and is often portrayed as painting pictures of Mary.

He is often shown

with an ox or a calf because these are the symbols of sacrifice -- thesacrifice Jesus made for all the world.

Luke is the patron

of physicians and surgeons.

Luke the Evangelist

|

Britannica Concise Encyclopedia: Luke the Evangelist

|

|

Christian Book Publisher |

Home > Library > Miscellaneous > Britannica Concise Encyclopedia

Saint Luke

(flourished 1st

century AD; feast day October 18)

In Christian tradition, the author of the thirdGospel and

the Acts of the Apostles. He wrote in Greek and is considered the most literary

of theNew Testament writers. By his own account, he was

not an eyewitness to the ministry of Jesus. He was a companion to St. Paul, who called him the "beloved

physician," and he is believed to have accompanied Paul on missionary

journeys to Macedonia and Rome. Though little is known of his life, tradition

holds that he was a Gentile and a native of Antioch in

Syria and that he died a martyr.

![]()

![]()

Luke

|

Top

Home > Library > Religion

& Spirituality > Dictionary of Saints

Luke (1st century), evangelist. Almost all that we know of him comes

from the New Testament. He was a Greek physician

(Col. 4: 14), a disciple of St. Paul, and his

companion on some of his missionary journeys (Acts 16: 10 ff.; 20: 5 ff., 27–8)

and the author of both Acts and the third gospel, which he describes in his

idiomatic Greek as ‘the former treatise which I wrote’ (Acts 1: 1). The

traditions that he was one of the first members of the Christian community at

Antioch, testified by Eusebius, and a physician by profession, may well be

correct: less certain is the claim that he lived to the age of eighty-four and

died unmarried. Much can be gleaned about his character from his writings. In

his Gospel the elements proper to him include much of the account of the Virgin Birth of Christ (Luke 1–2), some of the most moving

parables such as those of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son, with the words

of Christ in the Passion to the women ofJerusalem and

to the Good Thief. All these elements underline the compassion of Christ, which

together with Luke's emphasis on poverty, prayer, and purity of heart make up

much of his specific appeal to the Gentiles, for whom he wrote this Gospel of the Saviour of the world. Women figure more

prominently in Luke's gospel than in any other, for example, Mary, Elizabeth, the widow of Nain, and the woman who was a sinner.